The Gambia, officially the Republic of the Gambia, is a country in West Africa that is almost entirely surrounded by Senegal with the exception of its western coastline along the Atlantic Ocean. It is the smallest country in mainland Africa.

Gambia was a hub for the slave trade during the 16th and 17th centuries. However, by the 19th century, the country’s role in the slave trade had significantly declined, and it became an important center for commerce and trade with Europeans.

In the early 19th century, the Gambia was primarily under the control of the Mandinka empire, which was centered in the interior. The empire was known for its strong military and economic power and had established trade relations with European powers, particularly the British.

The British established a settlement in Banjul in 1816, and by the mid-19th century, the Gambia became a British colony. The British were primarily interested in the Gambia for its strategic location as a trading post and for its potential as an agricultural producer.

In the late 19th century, the Gambia experienced significant economic growth, driven primarily by the production of peanuts, which became the country’s primary export crop. The British introduced new farming techniques and infrastructure, such as railways and roads, which helped to increase production and trade.

Despite this economic growth, the Gambia remained under British control until it gained independence in 1965. The legacy of colonialism, however, has had a significant impact on the country’s political, economic, and social development.

The Economy of Gambia

The economy of The Gambia, like other African countries at the time, was very heavily oriented towards agriculture. Reliance on the groundnut became so strong that it made up almost the entirety of exports, making the economy vulnerable. Groundnuts were the only commodity subject to export duties; these export duties resulted in the illegal smuggling of the product to French Senegal.

Attempts were made to increase the production of other goods for export: the Gambian Poultry Scheme pioneered by the Colonial Development Corporation aimed to produce twenty million eggs and one million lb of dressed poultry a year. The conditions in The Gambia proved unfavorable and typhoid killed much of the chicken stock, drawing criticism to the corporation.

History

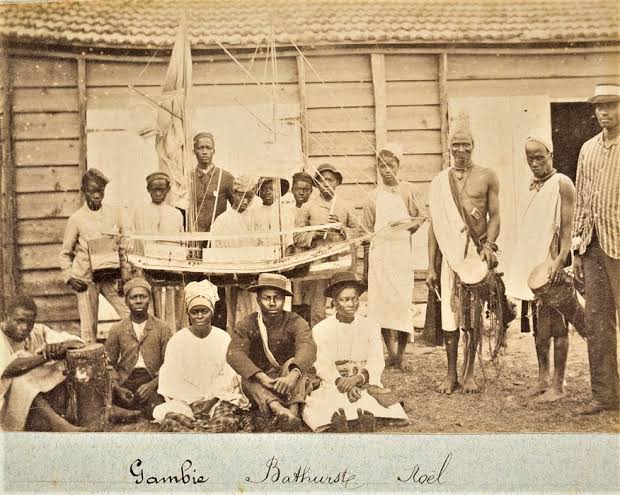

The foundation of the colony was Fort James and Bathurst, where British presence was established in 1815 and 1816, respectively. For various periods in its existence, it was subordinate to the Sierra Leone Colony. However, by 1888 it was a colony in its own right with a permanently appointed Governor.

The boundaries of the territory were an issue of contention between the British and French authorities due to the proximity to French Senegal. Additionally, on numerous occasions, the British government had attempted to exchange it with France for other territories, such as on the upper Niger River.

France and Britain agreed in 1889 in principle to set the boundary at 10 km (6.2 miles) north and south of the river and east to Yarbutenda, the furthest navigable point on the river Gambia. This was followed by the dispatch of a joint Anglo-French Boundary Commission to map the actual border. However, on its arrival in the area in 1891, the Boundary Commission was met with resistance by local leaders whose territories they were coming to divide. The commission could nevertheless rely on British naval power: British ships bombed the town of Kansala to force the Gambians to back off, and according to 1906 The Gambia Colony and Protectorate: An Official Handbook, men and guns from three warships landed on the riverbanks “as a hint of what the resisters had to expect in the event of any continued resistance.”

The colony ended in 1965 when The Gambia became an independent state within the Commonwealth of Nations, with Dawda Jawara as Prime Minister.

European colonization

The first Europeans in the Gambia River regions, the Portuguese, established trading stations in the late 1400s but abandoned them within a century. Trade possibilities in the next two centuries drew English, French, Dutch, Swedish, and Courlander trading companies to western Africa.

A struggle ensued throughout the 18th century for prestige in Senegambia between France and England, although trade was minimal, and no chartered company made a profit. This changed in 1816 when Capt. Alexander Grant was sent to the region to reestablish a base from which the British Navy could control the slave trade. He purchased Banjul Island (St. Mary’s) from the king of Kombo, built barracks, laid out a town, and set up an artillery battery to control access to the river. The town, Bathurst (now Banjul), grew rapidly with the arrival of traders and workers from Gorée and upriver. The Gambia was administered as a part of British West Africa from 1821 to 1843. It was a separate colony with its own governor until 1866 when control was returned to the governor-general at Freetown, Sierra Leone, as it would remain until 1889.

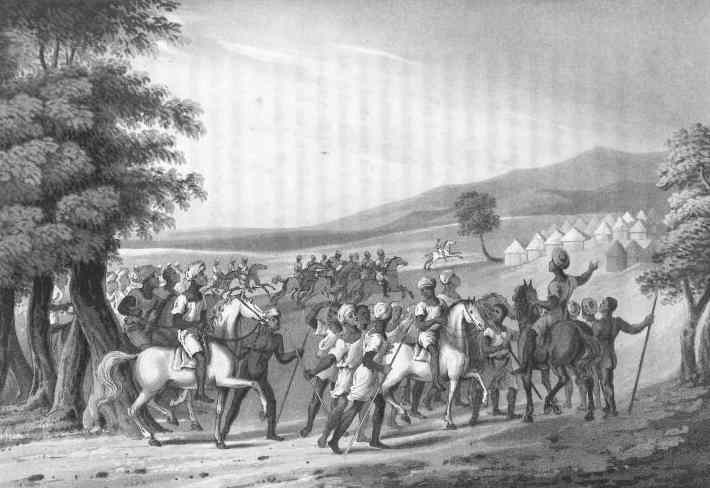

British domination of the riverine areas seemed assured after 1857, but the increasing importance of peanut cultivation in Senegal prompted a new imperialism. By 1880 France controlled Senegal; in the 1870s the British attempted twice to trade the Gambia to France, but opposition at home and in the Gambia foiled these plans. Complicating matters was the series of religious conflicts, called the Soninke-Marabout Wars, lasting a half century. Only one Muslim leader, Maba, emerged who could have unified the various kingdoms, but he was killed in 1864. By 1880 the religious aspect had all but disappeared, and the conflicts were carried on by war chiefs such as Musa Mollah, Fodi Silla, and Fodi Kabba.

Gambia and the Slave Trade

The suppression of the slave trade had a significant impact on the Gambia in the 19th century. Prior to the 19th century, the Gambia was one of the main centers of the transatlantic slave trade, with Europeans and African traders capturing and selling slaves from the region to the Americas and Europe.

In the early 19th century, the British government began to take steps to suppress the slave trade, and in 1807, the British Parliament passed a law banning the transatlantic slave trade. The British established a naval blockade along the coast of West Africa to intercept slave ships and seize their cargoes, and also established treaties with local rulers to prevent trade.

The suppression of the slave trade had a significant impact on the Gambia. The number of slaves being exported from the region declined sharply, and many traders switched to other commodities, such as palm oil and groundnuts, as a source of income. This shift had important consequences for the economy and society of the Gambia, as it led to the growth of new industries and the development of new forms of labor.

The suppression of the slave trade also had political consequences. The British used their naval power and their influence with local rulers to extend their control over the region, and the Gambia became a British colony in 1843. The British also established a network of trading posts and forts along the river, which further increased their influence and control.

Timeline

1783 - 1856 The first Treaty of Versailles gave Great Britain possession of the Gambia River, but the French retained a tiny enclave at Albreda on the river's north bank. This was finally ceded to the United Kingdom

1888 - The Gambia became a separate colony

1889 - An agreement with the French Republic established the present boundaries. The Gambia became a British Crown colony called British Gambia, divided for administrative purposes into the colony and the protectorate

1965 - The Gambia achieved independence, as a constitutional monarchy within the Commonwealth, with Elizabeth II as Queen of the Gambia, represented by the Governor-General

1970 - The Gambia became a republic within the Commonwealth, following a second referendum

1982 - 1989 Senegal and the Gambia signed a treaty of confederation. The Senegambia Confederation aimed to combine the armed forces of the two states and unify their economies and currencies. After just seven years, the Gambia permanently withdrew from the confederation

2013 -The Gambian interior minister announced that the Gambia would leave the Commonwealth immediately, ending 48 years of membership in the organization

2017 -The Gambia began the process of returning to its membership of the Commonwealth

2018 - Gambia officially rejoined the Commonwealth.

Christian Missionary Impact

Christian missionary activities in The Gambia in the 19th century had a significant impact on the country in several ways.

One of the primary impacts of Christian missionary activities was the spread of Christianity in The Gambia. The first Christian missionaries arrived in The Gambia in the early 19th century, and they focused on converting the local population to Christianity. They established churches, schools, and other institutions to promote the Christian faith, and over time, many Gambians converted to Christianity.

The Christian missionaries also played a key role in the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in The Gambia. They campaigned against slavery and worked with the British authorities to enforce anti-slavery laws. They also established schools and other educational institutions to educate the local population about the evils of slavery and to promote freedom and equality.

In addition, the Christian missionaries contributed to the development of education in The Gambia. They established schools and provided education to Gambians who would otherwise not have had access to it. This had a significant impact on the country’s development, as educated Gambians were able to take up leadership positions in government and other sectors.

However, the Christian missionaries also faced significant challenges in The Gambia. Many Gambians were resistant to their efforts to convert them to Christianity, and there were often tensions between Christians and Muslims in the country. Some Muslim leaders saw the Christian missionaries as a threat to their traditional way of life and resisted their activities.

Overall, the Christian missionary activities in The Gambia in the 19th century had a significant impact on the country’s development. They played a key role in the spread of Christianity, the abolition of slavery, and the development of education. However, they also faced significant challenges and opposition from some segments of the population.

The Soninke-Marabout wars and jihadists

The Soninke-Marabout wars were a series of conflicts that occurred in West Africa in the 19th century. The Soninke people were a group of farmers and traders who lived in the region, while the Marabouts were Islamic religious leaders who had gained significant political power. The wars were fought over control of land, resources, and political influence.

During this period, several jihadist leaders emerged in West Africa, including Usman Dan Fodio and El Hajj Umar Tall. Usman Dan Fodio was a Muslim scholar and preacher who led a jihad in northern Nigeria in the early 19th century. He established the Sokoto Caliphate, which became one of the largest states in Africa at the time. El Hajj Umar Tall was another jihadist leader who fought in West Africa during the 19th century. He established the Toucouleur Empire in what is now Senegal and Mali.

Both Usman dan Fodio and El Hajj Umar Tall sought to establish Islamic states that would be based on Sharia law. They were also opposed to the influence of European colonial powers in the region. The jihadist movements that they led had a significant impact on the history of West Africa, and their legacies continue to be felt in the region today.

Colonial government’s reaction to religious disturbances, 1850 to 1880

The colonial government’s reaction to religious disturbances in the period of 1850 to 1880 varied depending on the specific situation and the location of the colony. However, some general trends can be observed.

In many colonies, the colonial government tended to take a hands-off approach to religious matters, allowing local communities to practice their religion as they saw fit. However, this approach could sometimes lead to conflicts between different religious groups.

When religious conflicts did arise, colonial governments typically sought to maintain order and prevent violence. They might intervene in various ways, such as by deploying police or military forces to maintain peace, or by negotiating with religious leaders to try to resolve disputes peacefully.

In some cases, colonial governments took more active measures to regulate religion. For example, they might enact laws to restrict certain religious practices or to prevent the spread of what they considered to be “harmful” religious ideas. These measures were often motivated by concerns about maintaining social order or preserving the colonial power’s control over its subjects.

In British colonies, the government often adopted a policy of non-interference in religious affairs, except in cases where public order was threatened. For example, during the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857 in India, the British government intervened to quell the uprising, which had a religious dimension. However, in general, the British colonial government preferred to let religious communities manage their own affairs.

In French colonies, the government pursued a policy of assimilation, which involved imposing French culture and values on the local population. As part of this policy, the French colonial authorities suppressed traditional religious practices and encouraged the adoption of Christianity. When religious disturbances occurred, the French government often took a heavy-handed approach, using force to suppress dissent.

In Portuguese colonies, the government also pursued a policy of assimilation, but with a focus on Catholicism rather than French culture. The Portuguese authorities often intervened in religious affairs, sometimes using force to suppress non-Catholic practices. In some cases, this led to violent clashes between the colonial authorities and local populations.

African Anti-colonial Resistance

Resistance to European colonialism was a widespread phenomenon throughout Africa, as many societies and communities fought against the imposition of foreign rule and exploitation. Foday Kombo Sillah, Foday Kabbah Dumbuya, and Musa Molloh Baldeh were just a few of the many African leaders who played important roles in resisting colonialism.

Foday Kombo Sillah was a prominent anti-colonial leader in the Gambia during the early 20th century. He was a member of the Mandinka ethnic group and played a key role in organizing resistance against British colonial rule. He was particularly active in opposing the colonial government’s forced labor policies, which required Gambians to work on infrastructure projects for minimal pay. Sillah was also involved in the formation of the Gambia Native Association, a political organization that advocated for Gambian rights and autonomy.

Foday Kabbah Dumbuya was another anti-colonial leader in Sierra Leone during the early 20th century. He was a member of the Temne ethnic group and was particularly active in opposing British efforts to impose colonial taxes on local communities. Dumbuya was also involved in the formation of the Sierra Leone Progressive Association, a political organization that advocated for Sierra Leonean rights and autonomy.

Musa Molloh Baldeh was an important anti-colonial leader in Guinea during the mid-20th century. He was a member of the Fula ethnic group and played a key role in organizing resistance against French colonial rule. Baldeh was particularly active in opposing the forced conscription of Guinean men into the French army during World War II. He was also involved in the formation of the Guinean Democratic Party, which advocated for Guinean independence and self-rule.

Overall, these and other anti-colonial leaders played vital roles in resisting European colonialism in Africa. Their efforts helped to lay the groundwork for African independence movements and the eventual decolonization of the continent.

Independence

In anticipation of independence, efforts were made to create internal self-government. The 1960 Constitution created a partly elected House of Representatives, with 19 elected members and 8 chosen by the chiefs. This constitution proved flawed in the 1960 elections when the two major parties tied with 8 seats each. With the support of the unelected chiefs, Pierra Sarr N'Jie of the United Party was appointed Chief Minister. Dawda Jawara of the People's Progressive Party resigned as Minister of Education, triggering a Constitutional Conference arranged by the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

The Constitutional Conference paved the way for a new constitution that granted a greater degree of self-government and a House of Representatives with more elected members. Elections were held in 1962, with Jawara's Progressive Party securing a majority of the elected seats. Under the new constitutional arrangements, Jawara was appointed Prime Minister: a position he held until it was abolished in 1970.

Following agreements between the British and Gambian governments in July 1964, The Gambia became independent on 18 February 1965.