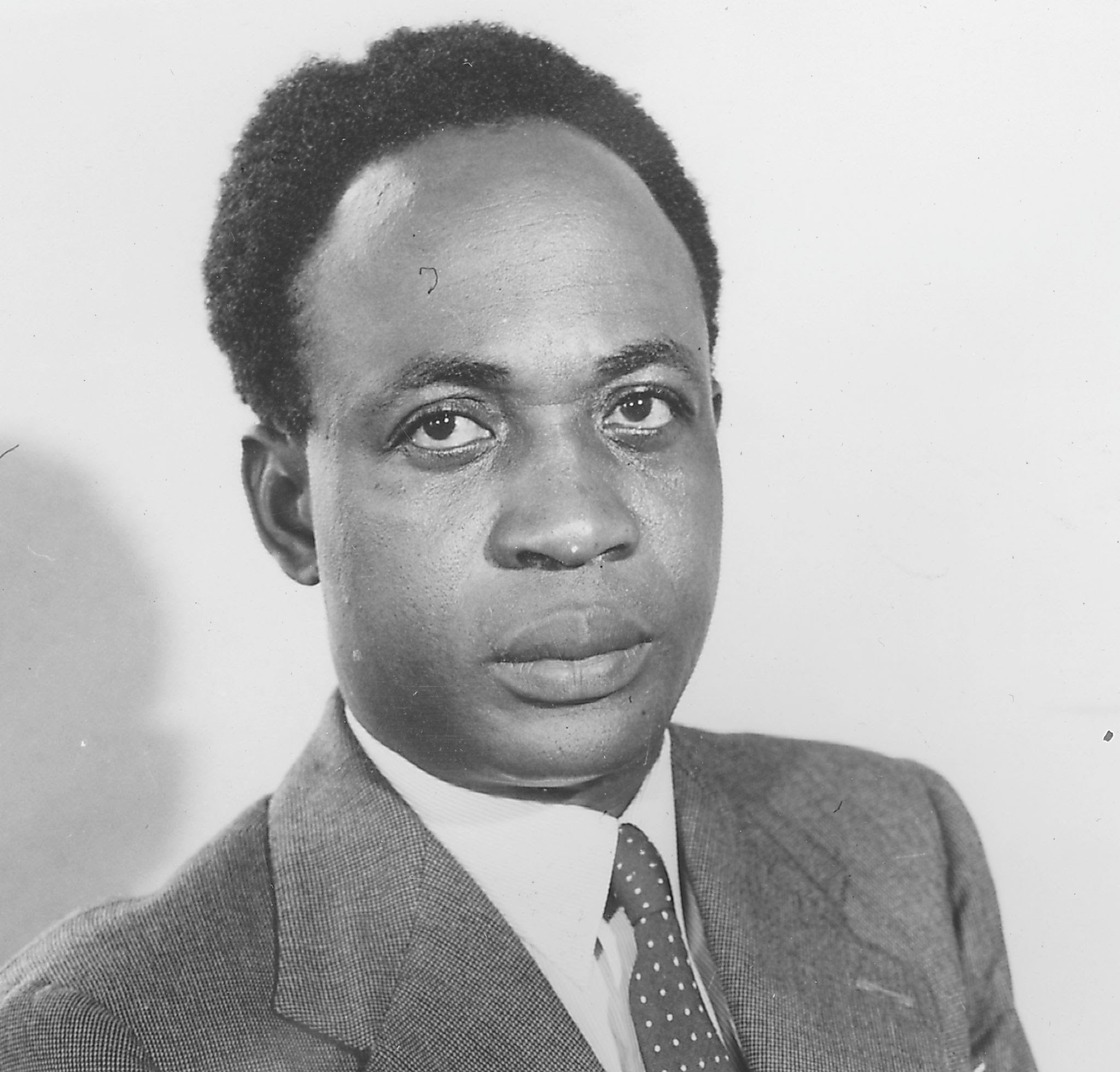

Kwame Nkrumah, (born September 1909, Nkroful, Gold Coast [now Ghana]—died April 27, 1972, Bucharest, Romania). A Ghanaian nationalist leader who led the Gold Coast’s drive for independence from Britain and presided over its emergence as the new nation of Ghana. He headed the country from independence in 1957 until he was overthrown by a coup in 1966.

Early years

Kwame Nkrumah’s father was a goldsmith and his mother was a retail trader. Baptized a Roman Catholic, Nkrumah spent nine years at the Roman Catholic elementary school in nearby Half Assini. After graduation from Achimota College in 1930, he started his career as a teacher at Roman Catholic junior schools in Elmina and Axim and at a seminary.

Increasingly drawn to politics, Nkrumah decided to pursue further studies in the United States. He entered Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in 1935 and, after graduating in 1939, obtained master’s degrees from Lincoln and from the University of Pennsylvania. He studied the literature of socialism, notably Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, and of nationalism, especially Marcus Garvey, the Black American leader of the 1920s. Eventually, Nkrumah came to describe himself as a “nondenominational Christian and a Marxist socialist.” He also immersed himself in political work, reorganizing and becoming president of the African Students’ Organization in the United States and Canada. He left the United States in May 1945 and went to England, where he organized the 5th Pan-African Congress in Manchester.

Meanwhile, in the Gold Coast, J.B. Danquah formed the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) to work for self-government by constitutional means. Invited to serve as the UGCC’s general secretary, Nkrumah returned home in late 1947. As general secretary, he addressed meetings throughout the Gold Coast and began to create a mass base for the new movement. When extensive riots occurred in February 1948, the British briefly arrested Nkrumah and other leaders of the UGCC.

When a split developed between the middle-class leaders of the UGCC and the more radical supporters of Nkrumah, he formed in June 1949 the new Convention Peoples’ Party (CPP), a mass-based party that was committed to a program of immediate self-government. In January 1950, Nkrumah initiated a campaign of “positive action,” involving nonviolent protests, strikes, and noncooperation with the British colonial authorities.

Kwame Nkrumah U.S. Studies

By 1935, Nkrumah undertook advanced studies in the United States at Lincoln University, Pennsylvania. In 1939, he earned a BA in Economics and Sociology. By 1942, he earned a BA in Theology. By 1943, Nkrumah had earned an M.Sc. (Education), and an MA (Philosophy), and completed coursework for a Ph.D. degree at the University of Pennsylvania.

During his U.S. undergraduate studies, Nkrumah also pledged to the predominately African-American Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, an academic honor society. He is said to have introduced African traditional steps to the fraternity's stepping tradition, including cane stepping.

Kwame Nkrumah Organizes Pan-Africans in Europe

Arriving in London in May of 1945, Nkrumah organized the 5th Pan-African Congress in Manchester, England, and began networking through organizations like the West African Students' Union, where he served as vice president. This same year he officially changed his name from Francis Nwia-Kofi to Kwame Nkrumah.

By December 1947, Nkrumah had returned to his homeland as a teacher, scholar, and political activist. He became General Secretary of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), which explored strategies for gaining independence from colonial England. Under Nkrumah's leadership, the UGCC attracted local political support from farmers and women. Women did not have the right to vote in many traditional patriarchial societies and farmers who were not land-owners also did not have suffrage. In 1948, Accra, Kumasi, and other areas of the Gold Coast were experiencing general social unrest, which the British colonial government accredited to the UGCC. By 1949, Nkrumah had galvanized wide support and reorganized his efforts under the Convention People's Party (CPP).

Kwame Nkrumah advocated for constitutional changes. This included self-government, universal franchise without property qualifications, and a separate house of chiefs. Jailed by the colonial administration in 1950 for his political activism, the CPP's 1951 election sweep was followed by Nkrumah's release.

A devout Pan-Africanist, Nkrumah supported the African federation under the auspices of the United States of Africa. He also had meaningful dialogue with African intellectuals from the diaspora, including W.E.B. DuBois, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Marcus Mosiah Garvey. He also corresponded with Trinidadian C.L.R. James, whom he credited with teaching him how an "underground movement worked." Nkrumah played a pivotal role in developing the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, the same year he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize.

From prison to prime ministry

In the ensuing crisis, services throughout the country were disrupted, and Nkrumah was again arrested and sentenced to one year’s imprisonment. But the Gold Coast’s first general election (February 8, 1951) demonstrated the support the CPP had already won. Elected to Parliament, Nkrumah was released from prison to become leader of government business and, in 1952, prime minister of the Gold Coast.

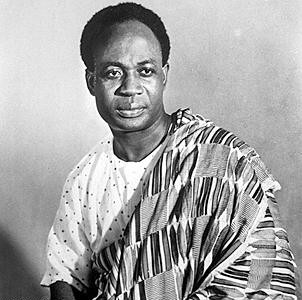

When the Gold Coast and the British Togoland trust territory became an independent state within the British Commonwealth—as Ghana—in March 1957, Nkrumah became the new nation’s first prime minister. In 1958 Nkrumah’s government legalized the imprisonment without trial of those it regarded as security risks. It soon became apparent that Nkrumah’s style of government was to be authoritarian. Nkrumah’s popularity in the country rose, however, as new roads, schools, and health facilities were built and as the policy of Africanization created better career opportunities for Ghanaians.

By a plebiscite of 1960, Ghana became a republic and Nkrumah became its president, with wide legislative and executive powers under a new constitution. Nkrumah then concentrated his attention on campaigning for the political unity of Black Africa, and he began to lose touch with realities in Ghana. His administration became involved in magnificent but often ruinous development projects so that a once-prosperous country became crippled with foreign debt. His government’s Second Development Plan announced in 1959, had to be abandoned in 1961 when the deficit in the balance of payments rose to more than $125 million. Contraction of the economy led to widespread labor unrest and to a general strike in September 1961. From that time Nkrumah began to evolve a much more rigorous apparatus of political control and to turn increasingly to the communist countries for support.

President of Ghana and afterward

The attempted assassination of Nkrumah at Kulugungu in August 1962—the first of several—led to his increasing seclusion from public life and to the growth of a personality cult, as well as to a massive buildup of the country’s internal security forces. Early in 1964, Ghana was officially designated a one-party state, with Nkrumah as the life president of both the nation and party. While the administration of the country passed increasingly into the hands of self-serving and corrupt party officials, Nkrumah busied himself with the ideological education of a new generation of Black African political activists. Meanwhile, the economic crisis in Ghana worsened and shortages of foodstuffs and other goods became chronic. On February 24, 1966, while Nkrumah was visiting Beijing, the army and police in Ghana seized power. Returning to West Africa, Nkrumah found asylum in Guinea, where he spent the remainder of his life. He died of cancer in Bucharest in 1972.