Mauritius has a rich history and is located in a very strategic place along the sea route between Europe and India. It has since then been a stopover for navigators. The Portuguese occupied the island between 1507 and 1513. The first settlement was though established by the Dutch between 1598 and 1710.

They landed and stayed at Mahebourg in the south-east of the island on their way to India for trade because fresh water, fruits and animals such as tortoise, fish and the dodo (now extinct) for food were easily available. They introduced sugarcane plants and manioc from Java. They cut down Ebony trees (now endemic) to sell back to Holland for furniture uses. Dutch colonization started in 1638 only and ended by 1710 due to unforeseen cyclones and pests like rats and mongoose, destroying their stock of grains.

One can still visit the Frederick Hendrik Museum and the Dutch routes in Grand Port.

The colonization of Mauritius by the Dutch followed a decision taken by the directors of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie – VOC) in 1637.

The VOC had exclusive legal rights on the island and its directors soon came to realize that the French and the British were also mulling over to occupy Mauritius as part of their colonial empire-building strategies.

If either of these rival nations claimed Mauritius, the colonial expansion of the Dutch in the Indian Ocean would have been seriously jeopardized.

Mauritius occupied a strategic position where Dutch ships sailing the Indian Ocean could find a safe stopover for provisions and crew rests. Moreover, from here they could round the Cape of Good Hope securely rather than sailing through passages near the coasts of Mozambique or of Madagascar where their fierce rival, the Portuguese, were extremely active.

It was also believed that Mauritius had enormous quantities of precious metals from which the Dutch East India Company could derive quick financial and economic benefits.

Cornelisz Simonsz Gooyer was nominated, on 15 December 1637, by the directors of the Amsterdam chamber of the Company as the first “commander” of Mauritius. He was in charge of a small occupying force working for the interest of the VOC and the colonization of Mauritius.

French Colonization and Development of Mauritius island

By the end of 1710, French navigators had already started visiting the island. They decided to settle down here in 1715. Guillaume Dufresne d’Arsel set up the French colony under the rule of the French East India Company.

He thus named Mauritius as Isle de France and Reunion Island as Ile Bourbon. Fertile soil on Isle de France was exploited while Ile Bourbon was used as a warehouse. With the arrival of Mahe de Labourdonnais in 1735, the island started developing productively into a colony. Slaves were brought from Africa and India, and more Bretons were encouraged to immigrate here to improve the island’s economic condition. French colonizers were allocated a plot of land and several slaves.

During the French colonization, inhabitants were motivated to grow cash crops and trade with the passers-by. Nutmeg and other spices, along with tobacco and tea, were also introduced. Sugar and Arrack were made out of cane plants. Roads across the island, buildings, houses, churches, schools and dispensaries were built. Port-Louis became the main port as access in and from Mahebourg was often affected by the Southeast Trade Winds.

Later the port developed into a naval base and a shipbuilding Centre during the Napoleonic wars. Buildings such as the Government House and the Line Barracks and the Chateau Mon Plaisir at Pamplemousses are some of the masterpieces of French architecture in Mauritius during French colonization.

British Colonization

The spice trade was the main reason for the presence of Europeans in the Indian Ocean during British colonization. British traders’ business started going down as the French were constantly trading in the Indian Ocean.

The fact that Mauritius island is at a focal point between the east and the west in the Indian Ocean, the British decided to capture the island. The Battle of Grand-Port in December 1810 brought defeat to the French who surrendered to the British which ushered the British colonization. The possession of the island by the British was legally confirmed by the Treaty of Paris in 1814. The British, however, allowed the French, Creoles and the slaves to stay back. By that time, the island was well-populated and the language mainly used was French and Mauritian Creole (Kreol Morisien which evolved while slaves were trying in vain to learn French).

The British changed the name of the island to its former name, Mauritius and continued developing it in the light of what the French had achieved to date.

The Start of British Rule and the End of Slavery? (1810)

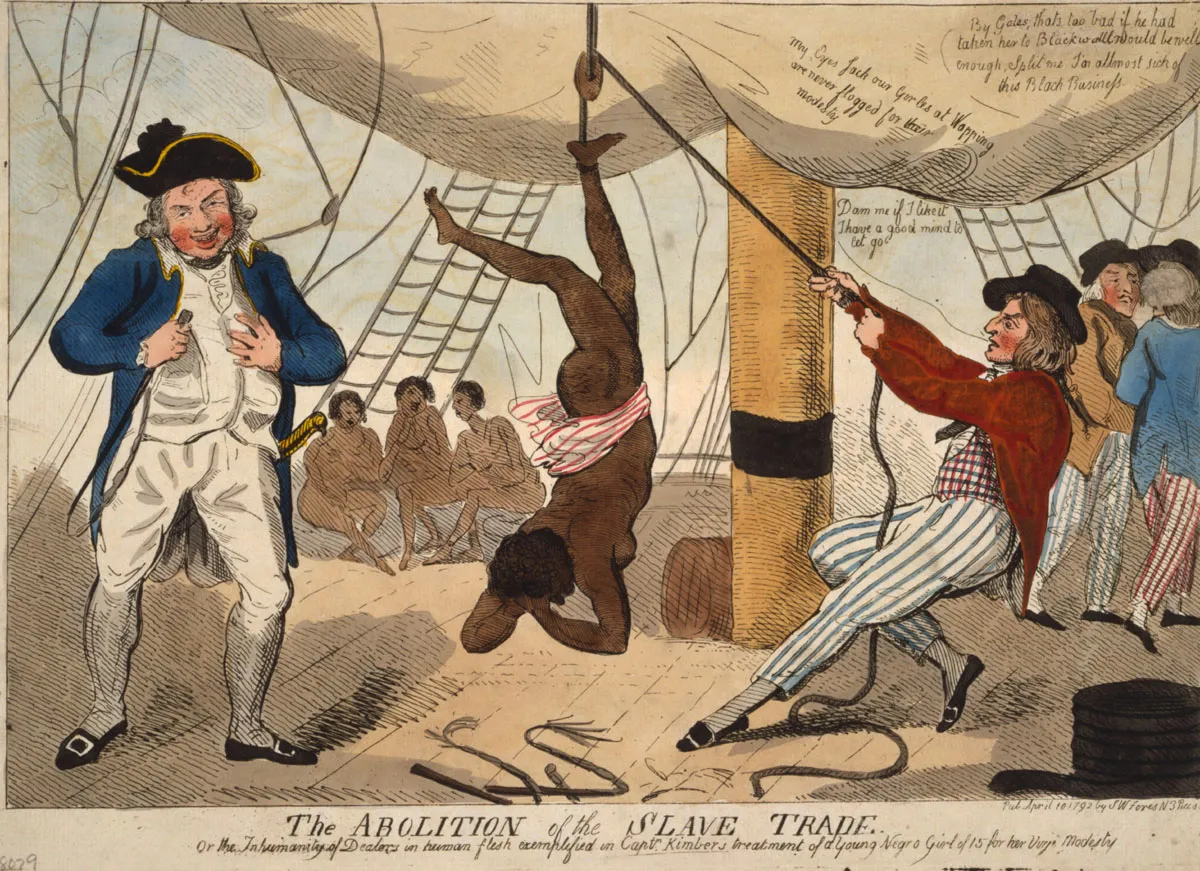

The British frequently raided the island and in 1810 finally engaged the French navy in a significant sea battle in Vieux Grand Port in the south. The five French ships, with support from shore, defeated the four British ones after a day of intense fighting. This rare naval victory is immortalized on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Six months later, the British returned with a significant land and sea force and successfully took Isle de France, restoring its Dutch name, Mauritius. Many of the rich whites refrained from defending their country. Their reward was an agreement that the British would permit them to maintain economic control of the country as well as their laws and customs. Unfortunately this included slavery even though it was banned under British law. The slave-owners used economic blackmail and bribery to maintain the status quo.

In 1814, Governor Farquhar proclaimed the abolition of the slave trade in Mauritius. However, slavery remained and new slaves were still smuggled into the country to try to maintain their declining numbers, despite efforts to replace them with the introduction of machinery. He also defied the British government by allowing the island to trade freely instead of exclusively with Britain and so the economy continued to flourish.

From Slavery to Slavery – Indentured Labour

By 1825, the shrinking and ageing slave population was being supplemented by indentured workers from India and China. However, the first group, believing that they had been recruited under false pretenses, rebelled against their cruel conditions and poor pay and were sent home. In 1826, a British inquiry into the slavery and racism by the dominant Franco-Mauritians against free-colures began. They in turn set up a parallel government and even managed to woo the coloured bourgeoisie, often slave-owners themselves, against the abolition of slavery.

In 1829 the post of Protector of Slaves was established to enforce their better treatment and Mauritius’ system of apartheid was officially abolished, though its practice continued for several years. Although the Franco-Mauritians fought it to the very end, slavery was finally abolished in 1835 but it wasn’t until 1839 that the emancipated slaves were free to leave the plantations. This they did in huge numbers, some to form villages and farm their own plots of land or fish, others to sink into dire poverty. No such fate awaited the slave-owners who were generously compensated for their loss by the British government.

The loss of the ex-slaves and the opportunity to expand the sugar plantations created an extreme shortage of labour that set costs soaring. To reduce wages to an absolute minimum and hence maximise profits, the plantation owners sought to flood the market with cheap labour from India. At the time many Indian’s suffered poverty under British administration and were happy to seek their fortune elsewhere. However, the immigration of coolies to Mauritius had many of the characteristics of the slave trade it replaced and was actually cheaper, indenture being a sort of voluntary slavery for a fixed period of time.

A momentous transformation in the population resulted. By 1861, the number of Indian immigrants outnumbered the white and coloured Mauritians by 192,634 to 117,416. However, as contracted labour, the coolies did not enjoy the same rights as the original population. Ironically, some even became servants of emancipated negro slaves. At the end of their contracts, many sought to and were encouraged to stay, started their own businesses and tried to climb the social strata.

In 1867, under the influence of the plantation owners, laws were passed which deteriorated the already inferior rights of the immigrants. For example, their travel within the island was restricted and they were required to carry passports with immediate detention if they were lost or left at home. To its shame Mauritius became an authoritarian police state with prison sentences for immigrants convicted of the most innocuous of crimes. It wasn’t until 1911 that indentured labour was effectively stopped by India, although a sugar boom in 1923 brought 1500 workers, but most went home within 3 years.

The First Steps to Democracy

The 1800s also saw many developments in Mauritius, supported by the wealth generated by the sugar industry. The Royal College, a world class educational establishment, produced many excellent scholars. Augmented by brilliant minds from Europe, Mauritius implemented all of the latest innovations of the day including the stamp-based postage system, telegraphy, cinemas, steam-power, railways and electricity generation.

In parallel, Mauritians, in particular the wealthy class, were demanding a greater say in the rule of their country. Ironically the poor too were mobilized when the government attempted to acquire lands to preserve the vanishing forests, protect species on the verge of extinction and safeguard water resources that were becoming contaminated and contributed to several significant epidemics.

Finally, in 1886, multi-party democracy began with the institution of parliamentary elections for 10 of the 27 members of the Council of Government. Only a few per cent of the population had the right to vote; immigrants, the poor and agricultural workers were excluded, even though in Britain the latter group had gained the right to vote in 1884. However, it would only be a matter of time before the numerically superior Indian population would rest political power from the wealthy minority as exhorted by Ghandi when he visited Mauritius on route from South Africa to India in 1901.

Then as now, Mauritius was stratified by ethnicity and class. The allegiance that dominated depended on the social, political or economic imperative of the day. Racism and apartheid, however, continued unabated as unwritten laws until the world-wide social revolutions of the 1960s and the radical reform of the Catholic Church which finally ended segregation in the pews.

Politically, the first two decades of the 1900s saw great men champion the cause of the unrepresented majority of the Mauritian population. Most were defeated and disillusioned in elections dominated by the Franco-Mauritians. During this time the number of Indo-Mauritians eligible to vote actually decreased, probably due to corrupt practices of the predominantly white magistrates.

The End of Franco-Mauritian Political Domination (1948)

The Great Depression of the 1930s led to severe deprivation among the working classes who were mobilised by the newly formed Labour party and the religious Bissoondoyal brothers. Strikes were organised on the sugar estates and the docks, paralysing the economy but were violently suppressed causing outrage in Mauritius and Britain. Subsequent reforms including a minimum wage for workers were largely disregarded by the sugar barons and strikes continued into the following decade.

During the 1940s the trend for colonies to demand self-rule was gaining momentum, with India gaining independence in 1947. In Mauritius, constitutional reform was debated from 1945-47 and finally in the 1948 elections any Mauritian resident over 21 who could read and write became eligible to vote. Thanks in large part to the mass education of Indo-Mauritians by the Bissoondoyal brothers, the total number of electors jumped from 12,000 to over 70,000. As a result, 17 of the 19 elected members of the Legislative Council were aligned to the Labour party. Together with the liberals, they enjoyed a majority despite the large number of nominated members appointed by the previous administration to make up the total of 34. This spelt the end of the political domination of the Franco-Mauritians who had to content themselves with control of the sugar industry.

The Road to Independence (1948-1968)

The next major step was independence. However, politics shifted from a class struggle to an ethnic one, fuelled in part by the fanatical racism of the editor in chief of a Franco-Mauritian newspaper. Independence, favoured by the British and the Labour party under the leadership of Dr Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, was greatly delayed by a united front of the ethnic minorities headed by Gaetan Duval, concerned by the possibility of future domination by the majority Hindus. After 20

years, compromise was finally reached whereby a new legislative assembly comprising of 62 elected members and 8 “best losers” was adopted; the latter being drawn from under-represented ethnic minorities.

Following the 1967 elections, Dr S Ramgoolam led the country on 12th March 1968 into nationhood. Gaetan Duval aligned his party with Labour and nation building became the order of the day.

Mauritius today

The latter years of the 20th century were marked by slowing economic growth as prosperity mostly and shifting political allegiances as different coalitions have been voted to power and ethnic considerations are returned to the foreground. Dr Mu also returned to enjoy his second visit to Mauritius in 1989 and was disappointed to see how much the lagoon, the fragile ecosystem within and including the coral reef, had degraded within 10 short years.

The emergence of global free-market economics, leading to the end of sugar and textile quotas, would leave Mauritius struggling to be competitive. To ensure a bright future, Vision 2020, the inspiring National Long Term Perspective Study, was started in 1994, facilitated by the Dutch under a Jugnauth government. However, he lost the election in 1995 to Ramgoolam’s son and publication was delayed until 1997. Unfortunately it and the National Development Strategy it inspired were ignored by Ramgoolam Junior and left on the shelf to gather dust.

[Riots of 1999]

In 2000, a coalition government, which reunited Jugnauth and Bérenger, sought to establish ICT, with significant help from India, as a new pillar of the economy. However, the vision of Cyber City mirroring Bangalore’s radiance would soon be obscured as opportunistic developers, many benefiting from nepotism, transformed the low density campus for innovation into a high rise monstrosity for call center's and financial services.

By 2003, the tourist sector was attracting around 700,000 visitors a year – the “green ceiling” limit proposed by Vision 2020 – mostly from France, Britain and South Africa. Further expansion was considered unwise as it would degrade the environment and the livelihoods and leisure of the local population as they competed for the use of the lagoon. However, lacking any foresight would

When the Ramgoolam and Duval Juniors regained power in 2005, they ignored the global shift towards eco-tourism and designated tourism as an engine of growth. Duval Junior destroyed Mauritius’ high class cachet by announcing a target of 2 million tourists by 2015, transforming Mauritius form an exclusive to mass-market destination. Increasing the head-count rather than per capita spend became his maniacal focus as he sold and leased State Land to hotel developers, while enriching nepotistic middlemen.