The paleontological record of human cultural artifacts in Malawi dates back more than 50,000 years, although known fossil remains of early Homo sapiens belong to the period between 8000 and 2000 BCE. These prehistoric forebears have affinities to the San people of southern Africa and were probably ancestral to the Twa and Fulani, whom Bantu-speaking peoples claimed to have found when they invaded the Malawi region between the 1st and 4th centuries CE. From then to about 1200 CE, Bantu settlement patterns spread, as did ironworking and the slash-and-burn method of cultivation. The identity of these early Bantu-speaking inhabitants is uncertain. According to oral tradition, names such as Kalimanjira, Katanga, and Zimba are associated with them.

With the arrival of another wave of Bantu-speaking peoples between the 13th and 15th centuries CE, the recorded history of the Malawi region began. These peoples migrated into the region from the north, interacting with and assimilating earlier pre-Bantu and Bantu inhabitants. The descendants of these peoples maintained a rich oral history, and, from 1500, written records were kept in Portuguese and English.

Among the notable accomplishments of the last group of Bantu immigrants was the creation of political states, or the introduction of centralized systems of government. They established the Maravi Confederacy in about 1480. During the 16th century the confederacy encompassed the greater part of what is now central and southern Malawi, and, at the height of its influence, in the 17th century, its system of government affected peoples in the adjacent areas of present-day Zambia and Mozambique. North of the Maravi territory, the Ngonde founded a kingdom about 1600. In the 18th century, a group of immigrants from the eastern side of Lake Malawi created the Chikulamayembe state to the south of the Ngonde.

The precolonial period witnessed other important developments. In the 18th and 19th centuries, better and more productive agricultural practices were adopted. In some parts of the Malawi region, shifting cultivation of indigenous varieties of millet and sorghum began to give way to more intensive cultivation of crops with a higher carbohydrate content, such as corn (maize), cassava (manioc), and rice.

The independent growth of indigenous governments and improved economic systems was severely disturbed by the development of the slave trade in the late 18th century and by the arrival of foreign intruders in the late 19th century. The slave trade in Malawi increased dramatically between 1790 and 1860 because of the growing demand for slaves on Africa’s east coast.

Swahili-speaking people from the east coast and the Ngoni and Yao peoples entered the Malawi region between 1830 and 1860 as traders or as armed refugees fleeing the Zulu states to the south. All of them eventually created spheres of influence within which they became the dominant ruling class. The Swahili speakers and the Yao also played a major role in the slave trade.

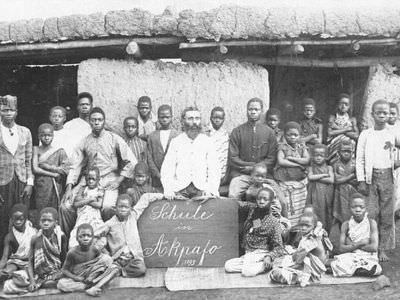

Islam spread into Malawi from the east coast. It was first introduced at Nkhotakota by the ruling Swahili-speaking slave traders, the Jumbe, in the 1860s. Traders returning from the coast in the 1870s and ’80s brought Islam to the Yao of the Shire Highlands. Christianity was introduced in the 1860s by David Livingstone and by other Scottish missionaries who came to Malawi after Livingstone’s death in 1873. Missionaries of the Dutch Reformed Church of South Africa and the White Fathers of the Roman Catholic Church arrived between 1880 and 1910.

Christianity owed its success to the protection given to the missionaries by the colonial government, which the British established after occupying the Malawi region in the 1880s and ’90s. British colonial authority was welcomed by the missionaries and some African societies but was strongly resisted by the Yao, Chewa, and others.

The British Colonization

In 1859 David Livingstone the Scottish explorer and missionary reached Lake Nyasa. Following him in 1873 two Scottish Presbyterian missionary societies built missions in the area. More missionaries followed and British merchants began to sell goods in the region. In 1883 Britain sent a consul to the area.

Gradually the British took control of Malawi. In 1889 they formed the Shire Highlands Protectorate and in 1891 most of Malawi was formed into the British Central African Protectorate. The first commissioner was Harry Johnston. The British ended the slave trade and created coffee plantations. In 1897 Johnston was replaced by Alfred Sharpe.

In 1907 the British named Malawi Nyasaland. Also in 1907, Nyasaland was given a legislative council. The commissioner was made a governor. Alfred Sharpe retired in 1910.

When the First World War began Germans from Tanzania invaded Nyasaland (Malawi) but they were repelled. However, in January 1915 a man named John Chilembwe led a rebellion in Malawi which was quickly crushed.

During World War II almost 30,000 Malawians served in the armed forces.

However, as the Africans were increasingly well educated they became more and more dissatisfied with being ruled by Europeans. In 1944 they formed the Nyasaland African Congress. In 1949 native Malawians were allowed to sit on the legislative council for the first time.

Then in 1953, the British joined Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), and Nyasaland (Malawi) into a single unit called the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

In 1958 Dr Hasting Banda became head of the African Congress, which was renamed the Malawi Congress Party in 1959. There were many protests against British rule and as a result, a state of emergency was declared. (During it Banda was imprisoned for a time).

However, the British now realized that independence for Malawi was inevitable. In 1961 the Malawian Congress Party won elections to the legislative council and in 1962 the British agreed to make Malawi independent. The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was dissolved in 1963. Malawi became independent on 6 July 1964.

Post-independence Malawi

The Banda regime, 1963–94

Soon after independence, a serious dispute arose between Banda, the prime minister, and most of his cabinet ministers. In September 1964 three ministers were dismissed and three others resigned in protest. Henry Chipembere, one of these ministers, escaped from house arrest and defied attempts at recapture, becoming the focus for antigovernment opinion until his death in 1975. On July 6, 1966, Malawi became a republic, and Banda was elected president; in 1971 he was made president for life.

Malawi’s 1966 constitution established a one-party state under the Malawi Congress Party (MCP), which in turn was controlled by Banda, who consistently and ruthlessly suppressed any opposition. From independence, the MCP government became a conservative, pro-Western regime, supported by a bicameral National Assembly whose members were elected within the single-party system.

Banda’s government improved the transport and communication systems, especially the road and railway networks. There was also much emphasis on cash crop production and food security; the estate sector (which produced tobacco, tea, and sugar) met expectations, but smallholder production was not as successful, mainly because of the low prices offered by the Agricultural Development and Marketing Corporation (ADMARC), the state organization that had the monopoly on marketing smallholder produce. In addition, the cost of fertilizer, all of which was imported and also dominated by ADMARC, rendered smallholder agriculture expensive.

For more than 10 years, Malawi was able to prosper economically before being felled by a confluence of external factors. In 1980, in an effort to improve the country’s economic situation and broaden regional ties, Malawi joined the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (later the Southern African Development Community), a union of black majority-ruled countries near minority-ruled South Africa that wished to reduce their dependence on that country. Banda refused to sever formal diplomatic ties with the apartheid regime in South Africa, however—a decision that was not popular with the other leaders in the region.

James Clyde Mitchell

Kenneth Ingham

On March 8, 1992, a pastoral letter written by Malawian Catholic bishops expressing concern at—among other things—the poor state of human rights, poverty, and their effects on family life was read in churches throughout Malawi. This act served to encourage underground opposition groups that had long waited for an opportunity to mount an open and vigorous campaign for multiparty democracy; exile groups also intensified their demands for political reform. Additional pressure was applied by international donors, who withheld financial aid. By the end of 1992, two internally based opposition parties, the Alliance for Democracy and the United Democratic Front (UDF), had emerged, and Banda agreed to hold a national referendum to determine the need for reform. Advocates for change won an overwhelming victory, and in May 1994, the first free elections in more than 30 years took place. Banda was defeated by Bakili Muluzi of the UDF by a substantial margin, and the UDF won a majority of seats in the National Assembly. Although no longer active, Banda remained head of the MCP until his death in November 1997.

Malawi since 1994

A new constitution, officially promulgated in 1995, provided the structure for transforming Malawi into a democratic society. Muluzi’s first term in office brought the country greater democracy and freedoms of speech, assembly, and association—a stark contrast to life under Banda’s regime. Muluzi’s administration also promised to root out government corruption and reduce poverty and food shortages in the country, although this campaign met with limited success. Muluzi pursued good relations with a number of Arab countries, toward most of which Banda had been particularly cool; he also sought to play a more active role in African affairs than his predecessor. Muluzi was reelected in 1999, but his opponent, Gwandaguluwe Chakuamba, challenged the results. The aftermath of the disputed election included demonstrations, violence, and looting. During Muluzi’s second term, he drew domestic and international criticism for some of his actions, which were viewed as increasingly autocratic.

Malawi’s international standing was bolstered in 2000, when the country’s small air force responded quickly to the flooding crisis in the neighboring country of Mozambique, rescuing upward of 1,000 people. However, the country was not as quick to respond to a severe food shortage at home, first noted in the latter half of 2001. By February 2002 a famine had been declared, and the government was scurrying to find enough food for its citizens. Unfortunately, much international aid was slow to arrive in the country—or was withheld entirely—because of the belief that government mismanagement and corruption contributed to the food shortage. In particular, some government officials were accused of selling grain from the country’s reserves at a profit to themselves prior to the onset of the famine.

Muluzi was limited to two terms as president, despite his efforts to amend the constitution to allow further terms. In 2004 his handpicked successor, Bingu wa Mutharika of the UDF, was declared the winner of an election tainted by irregularity and criticized as unfair. Mutharika’s administration quickly set out to improve government operations by eliminating corruption and streamlining spending. To that end, Mutharika dramatically reduced the number of ministerial positions in the cabinet and initiated an investigation of several prominent UDF party officials accused of corruption, leading to several arrests. His actions impressed international donors, who resumed the flow of foreign aid previously withheld in protest of the financial mismanagement and corruption of Muluzi’s administration.

By that time the country had been negatively affected by the HIV/AIDS crisis and the lack of such requisites as economically viable resources, an accessible and well-utilized educational system, and an adequate infrastructure—issues that continued to hamper economic and social progress. However, Mutharika’s administration showed potential for leading Malawi on a path of meaningful political reform, which in turn promised to further attract much-needed foreign aid.