Early history

The precolonial history of Guinea-Bissau has not been fully documented in the archaeological record. The area has been occupied for at least a millennium, first by hunters and gatherers and later by decentralized animist agriculturalists who used iron implements for their rice farming. Ethnogenesis and interethnic dynamics in the 13th century began to push some of these agriculturists closer to the coast, while others intermixed with the intrusive Mande as the Mali empire expanded into the area. Gold, slaves, and marine salt were exported from Guinea toward the interior of the empire. As Mali strengthened, it maintained local, centralized control through its secondary kingdoms and their farms (local kings), whose task was to maintain local law and order and the flow of tributary goods and soldiers as needed. In the case of what is now Guinea-Bissau, this state was known as Kaabu, and the agriculturists often suffered in their subordinate relationship to its economic and military needs. The Fulani entered the region as semi-nomadic herders as early as the 12th century, although it was not until the 15th century that they began to arrive in large numbers. Initially, they were also subordinate to the kingdom of Kaabu, although there was something of a symbiotic relationship between the Mande farmers and traders and the Fulani herdsmen, both of whom followed a version of Africanized Islam.

Contacts with the European world began with the Portuguese explorers and traders who arrived in the first half of the 15th century. Notable among these was Nuño Tristão, a Portuguese navigator who set out in the early 1440s in search of slaves and was killed in 1446 or 1447 by coastal inhabitants who were opposed to his intrusion. The Portuguese monopolized the exploration and trade along the Upper Guinea coast from the later 15th and early 16th centuries until the French, Spanish, and English began to compete for Africa's wealth

Tens of thousands of Guineans were taken as slaves to Cape Verde to develop its plantation economy of cotton, indigo, orchil, and urzella dyes, rum, hides, and livestock. Weaving and dyeing slave-grown cotton made it possible to make panos, unique textiles woven on a narrow loom and usually constructed of six strips stitched together, which became standard currency for regional trade in the 16th century. Lançados (freelance Cape Verdean traders) participated in the trade of goods and slaves and were economic rivals of the Portuguese. At times the lançados were so far beyond Portuguese control that severe penalties were imposed to restrict them. Often these measures either dried up the trade to the crown or caused even more brash smuggling.

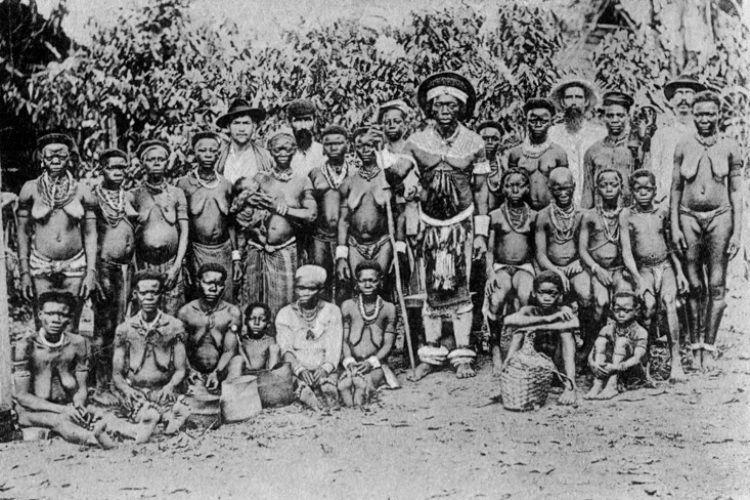

In Guinea-Bissau and neighboring territories, slaves were captured among the coastal peoples or among interior groups at war. While Kaabu was ascendant, the Fulani were common victims. In 1867 the kingdom of Kaabu was overthrown by the Fulani, after which the number of Mande increased on the slave ships’ rosters. Groups of slaves were bound together in coffles and driven to the coastal barracoons (temporary enclosures) at Cacheu, Bissau, and Bolama by grumetes (mercenaries). There the prices were negotiated by tangomãos (who functioned as both translators and mediators), and slaves were sold to the lançados and senhoras (slave-trading women of mixed parentage).

Cape Verde was used as a secure offshore post for the trade of goods from Africa, which included slaves, ivory, dyewoods, kola nuts, beeswax, hides, and gold, as well as goods destined for Africa, such as cheap manufactured items, firearms, cloth, and rum. From the islands of Cape Verde, the Portuguese maintained their coastal presence in Guinea-Bissau. Tens of thousands of slaves were exported from the coast to the islands and onto the New World, destined for major markets such as the plantations in Cuba and northeastern Brazil.

European rivalries on the Guinea coast long threatened the Portuguese position in the islands, where irregular commerce, corruption, and smuggling became routine. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, there was an English initiative to abolish or slow the slave trade, and the United States mounted a halfhearted parallel effort. From 1843 to 1859 the U.S. Navy stationed the Africa Squadron, a fleet of largely ineffective sailing vessels meant to intercept American slavers, at Cape Verde and along the Guinea coast. However, political indifference, legal loopholes, and flags of convenience undermined this program. After four centuries of slaving, the Portuguese gradually abandoned the practice by the late 1870s, although it was replaced by oppressive forced labor and meager wages to pay colonial taxes.

Colonial period

Despite the five centuries of contact between Guineans and the Portuguese, one cannot truly speak of a deeply rooted colonial presence until the close of the 19th century. The long-lasting joint administration of Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau was terminated in 1879 and both became separate colonial territories: Cape Verde and Portuguese Guinea. However, the European rivalries for control of the larger Guinea region only intensified. Long-term Anglo-Portuguese bickering over the ownership of Bolama was finally resolved when U.S. Pres. Ulysses S. Grant adjudicated the dispute in Portugal’s favor in 1870. However, the Franco-Portuguese conflict over the Casamance region was resolved in France’s favor in May 1886.

The struggle for dominance around Guinea-Bissau fell within the context of the greater scramble for Africa that characterized the 1884–85 Berlin Congress, which saw English demands for Guinean territories to the south and French demands along the north and east. The Guinean people were certainly not consulted about such matters, and they resisted, revolted, and mutinied by any available means whenever possible. The Berlin Congress had called for the demonstration of “effective occupation,” though, and, in an attempt to satisfy this condition, Capt's brutal “pacification” campaign. João Teixeira Pinto—with the employed support of an African mercenary force—was conducted from 1913 to 1915. The killings and severe punitive measures exacted by the Portuguese and their mercenaries brought a widespread outcry. Nevertheless, the Portuguese continued their pacification efforts against the Guinean population, especially the coastal peoples, and launched three more major campaigns of pacification, the latest of which was undertaken in January 1936.

During World War II many Africans gained military and political experience while fighting with and for the colonial powers. In the wake of that war came the emergence of African nationalist movements, and, by the early 1960s, most western African countries had achieved independence through protest, petition, demonstration, and other largely peaceful means. To avoid criticism of its colonial policies in Africa, in 1951 the Portuguese had redefined their colonies’ status to that of overseas provinces. The African population of Guinea-Bissau did not perceive these changes as meaningful, however, and some members of the colonial population began agitation for complete independence from Portugal for both Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde.

Liberation struggle

In 1956 a group of Cape Verdeans founded the National Liberation Party for Guinea and Cape Verde—the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde; PAIGC). Most notable of its leaders was Amílcar Cabral, a brilliant revolutionary theoretician. At first, the PAIGC’s goal was to achieve independence through peaceful means of protest; however, in August 1959 the Portuguese responded to a dockworkers’ strike with violence, killing and wounding numerous demonstrators, which convinced the PAIGC that only a rurally based armed struggle would be sufficient to end the colonial and fascist regime. After a period of military training and political preparation, the PAIGC launched its armed campaign in January 1963 and showed steady military progress thereafter. The creation of the People’s Revolutionary Armed Force (Forças Armadas Revolucionarias do Povo) and the Local Armed Forces (Forças Armadas Locais) provided for both offensive and defensive military action.

Despite being confronted by large numbers of Portuguese soldiers and their accompanying military technology, the PAIGC gained control of some two-thirds of the country, with the Portuguese colonial army under Gen. António de Spínola surviving only in the major towns and heavily fortified bases. On January 20, 1973, Cabral was assassinated; nevertheless, on September 24, 1973, independence was declared. This event, compounded by the drawn-out wars in Portugal’s other overseas provinces, precipitated a crisis that led to a successful coup in Lisbon on April 25, 1974. Portugal’s new government soon began negotiating with African nationalist movements.

Independence of Guinea-Bissau

Full independence was achieved by Guinea-Bissau on September 10, 1974; Cape Verde achieved independence the following year. The Cape Verdean revolutionary comrades Luís de Almeida Cabral (half-brother of Amílcar Cabral) and Aristides Pereira became the first presidents of Guinea-Bissau and the Republic of Cape Verde, respectively. João (“Nino”) Vieira became the commander in chief of the armed forces of Guinea-Bissau.

In August 1978 Vieira assumed the position of prime minister in Guinea-Bissau following the accidental death of his predecessor, Francisco Mendes, in July. On November 14, 1980, Vieira led a military coup against Cabral, who was charged with abuse of power and sentenced to death; after negotiations, Cabral was released from that sentence and went into exile. The coup was deeply resented in Cape Verde and severed the military and political unity that had existed between the two countries. The Cape Verdean branch of the PAIGC was replaced by the African Party for the Independence of Cape Verde (Partido Africano para a Independência de Cabo Verde; PAICV), which eliminated reference to Guinea-Bissau.

With his ascent to power, Vieira faced difficult political and economic problems. Guinea-Bissau’s poverty required development aid from Portugal, which was in turn seeking to restore its economic relations with Guinea-Bissau. In addition, the poorly performing state-planned economic policy that had been adopted with independence was increasingly liberalized in subsequent years as attempts were made to improve the economy, but the shift toward a free-market economy was not universally embraced and became a source of political unrest.

Guinea-Bissau made the transition to a democratic, multiparty system in the early 1990s, and the country’s first free legislative and presidential elections were held in 1994. The PAIGC won a majority of legislative seats, while Vieira narrowly won his race.

In 1997 Guinea-Bissau joined the West African Economic Monetary Union and the Franc Zone. However, fiscal volatility caused in part by these actions contributed to political unrest that came to a head in 1998 when Vieira dismissed military chief of staff Brig. (later Gen.) Ansumane Mané. Almost immediately Mané initiated a revolt that was fueled by widespread frustration and opposition to Vieira. Most observers first thought that the mutineers would tire and Vieira would reemerge as the victor; instead, the conflict broadened. Various cease-fires were called and broken, and troops from Guinea, Nigeria, Senegal, and France intervened. After each round of fighting, Vieira became increasingly isolated in Bissau. In May 1999 he was forced to surrender and later went into exile in Portugal. Subsequent elections, deemed free and fair by international observers, brought to power the country’s first non-PAIGC government, led by Pres. Kumba Ialá.

Despite a democratic beginning, Ialá’s rule became increasingly repressive. Widespread discontent with the deteriorating economic and political climate led to his removal in a bloodless coup in September 2003. Soon after, Henrique Rosa, a businessman and virtual political newcomer, was sworn in as interim president. Under Rosa’s transitional government, legislative elections were held in 2004, moving Guinea-Bissau on course toward a stable, constitutional government. While forging political peace, Rosa was faced with the task of rebuilding the country’s infrastructure and improving the economy, both severely damaged from the civil war and years of political strife.

In March 2005 Ialá announced his intention to contest the elections scheduled for June of that year, although both he and Vieira—who had returned from exile in April—had been barred from politics in 2003. Both candidates were subsequently cleared to run for office in April. The following month, Ialá announced that he was in fact still president and staged a brief occupation of the presidential building. Defeated in the first round of polling, however, he eventually backed Vieira, who won a second round of elections held in July. Although supporters of the opposition raised allegations of fraud, the elections were declared by international observers to have been free and fair.

Ongoing political strife and economic challenges were compounded by drug smuggling, an increasing problem for Guinea-Bissau and other western African countries in the mid-2000s. With a geography favourable to smuggling and the inability to adequately protect its coastline and airspace, Guinea-Bissau was a particularly desirable target, and individuals in the upper echelons of the government, military, and other sectors were allegedly involved in drug trafficking.

Mounting conflict between the military elite and Vieira’s administration—fueled in part by ethnic tensions—generated increasing domestic instability, and in November 2008 Vieira survived an attack by mutinous soldiers that was described as an attempted coup. On March 2, 2009, Vieira was assassinated by soldiers who believed he was responsible for the death of the chief of the armed forces, Gen. Batista Tagme Na Waie, who had been killed in an explosion hours earlier. The military denied any intent to seize power, and, under the terms of the constitution, parliamentary leader Raimundo Perreira was sworn in to serve as interim president until elections could be held; they were eventually scheduled for June 28. On June 5, military authorities killed presidential candidate Baciro Dabo, former defense minister Helder Proenca, former prime minister Faustino Embali, and others, alleging that they were part of a group planning to overthrow the current government. Many senior PAIGC members were also detained as part of the operation to foil the alleged coup.

The tension and uncertainty surrounding the alleged coup and the military’s response to it did not interfere with the scheduled presidential election, which proceeded as planned on June 28. None of the 11 candidates were able to obtain a majority of votes, so election officials announced that the two front-runners—the PAIGC’s Malam Bacai Sanhá, who once briefly served as interim president, and former president Kumba Ialá—would face each other in a runoff election. In the second round of voting, held on July 26, 2009, Sanhá was victorious, receiving more than three-fifths of the vote.

Throughout his presidency, Sanhá was plagued by poor health and did not initiate much meaningful change in the unstable country. A short-lived military uprising occurred in April 2010, led by the deputy chief of staff, Maj. Gen. António N’djai, and former naval chief, Rear Adm. José Americo Bubo Na Tchuto, had been involved in a previous coup attempt and was one of the country’s high-ranking officials allegedly involved in drug trafficking. In October 2010 Sanhá surprised many with his decision to reinstate Na Tchuto as naval chief, a decision that was questioned and criticized by the international community.

On December 26, 2011, while Sanhá was out of the country for medical reasons, an apparent coup attempt was quickly put down. The alleged mastermind behind the plot was Na Tchuto; he was one of many people arrested for suspected involvement with the coup. While the aftermath of the attempted coup was still being dealt with, on January 9, 2012, the government announced that Sanhá had died in Paris, where he had been undergoing medical treatment. Perreira once again served as interim president until a new president could be elected. In February Prime Minister Carlos Gomes Júnior stepped down so that he could serve as the PAIGC’s presidential candidate in the upcoming election.

Nine candidates contested the presidential election, which was held on March 18, 2012. Although the voting process was peaceful and deemed free and fair by international observers, there were some causes for concern, including the murder of Col. Samba Diallo, the former chief of military intelligence, shortly after the polls closed, and accusations of fraud were lodged by several of the candidates, including former president Ialá. When results were announced a few days later, Gomes Júnior emerged as the top vote-getter, with 49 percent of the vote; his nearest challenger was Ialá, who garnered 23 percent. Since Gomes Júnior fell short of winning a majority, a runoff election between him and Ialá was scheduled for April 29, although Ialá said that he would boycott the second round of voting to protest the alleged fraud that he had previously complained about.

Before the runoff election could be held, however, a military coup occurred on April 12, and Gomes Júnior, interim president Perreira, and other government officials were arrested. Coup leaders stated that they did not plan on maintaining power and claimed that their action was necessary to prevent foreign aggression in the country and to counter alleged plans to downsize Guinea-Bissau’s military. The coup was widely condemned, and the African Union (AU) suspended Guinea-Bissau the next week. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) condemned the coup as well but negotiated with the coup leaders, with the goal of restoring constitutional order to the country. Negotiations did result in Perreira’s and Gomes Júnior’s being released and flown out of the country in late April, but talks broke down soon after that. As a result, on April 30 ECOWAS imposed sanctions on Guinea-Bissau and the leaders of the coup.

In the following weeks, the coup leaders and ECOWAS managed to reach an agreement regarding the restoration of civilian rule, and on May 11, 2012, the president of Guinea-Bissau’s National People’s Assembly, Manuel Serifo Nhamadjo, was named president of a transitional government that was intended to restore civilian rule within one year. Nhamadjo had finished third in the March presidential election and was asked by military leaders in April to lead a controversial two-year transitional government, but at the time he refused, denouncing the military’s proposal as being illegal.

The return to democratically elected civilian rule was stalled, as parliamentary and presidential elections, originally scheduled to take place in 2013, were delayed. When they finally occurred on April 13, 2014, the PAIGC made a strong showing: the party won slightly more than half of the legislative seats, and its presidential candidate, former finance minister José Mário Vaz, received about 41 percent of the vote. As Vaz did not secure an outright majority, he and the second-place candidate, independent Nuno Gomes Nabiam, who won about 25 percent of the vote, advanced to a runoff election held on May 18. Vaz again emerged victorious, winning about 62 percent of the vote. Citing the successful elections, the AU lifted its suspension on Guinea-Bissau on June 17, 2014. Vaz was inaugurated as president on June 23, 2014.

Vaz’s term saw much political turmoil, which included a lengthy power struggle between him and others in the PAIGC, more than half a dozen different prime ministers in five years, and a parliament unable to act. Parliamentary elections, held in March 2019, saw the PAIGC taking more seats than any other party. The first round of the presidential election was held on November 24, 2019. Former prime ministers Domingos Simões Pereira, representing the PAIGC, and Umaro Sissoco Embaló, representing the Movement for Democratic Alternation Group of 15 (Madem G-15) opposition party founded by former PAIGC members, were the two top vote-getters, taking about 40 percent and 28 percent respectively. Vaz, who ran as an independent, won little more than 12 percent.

Pereira and Embaló advanced to a runoff election held on December 29. Embaló was declared the winner with about 54 percent of the vote, although Pereira and the PAIGC voiced allegations of fraud and filed complaints with the Supreme Court. One, filed on February 26, 2020, was still pending when Embaló held his own inauguration ceremony on February 27. The next day he dismissed Prime Minister Aristides Gomes, replacing him with Nuno Gomes Nabiam, who took office on February 29. The legality of Embaló’s inauguration, however, was disputed by Pereira and the PAIGC because of the pending case with the Supreme Court, and Gomes rejected his dismissal as being unlawful. Meanwhile, the PAIGC-dominated parliament, the National People’s Assembly, did not recognize Embaló’s presidency and on February 28 swore in Cipriano Cassamá, the speaker of parliament, to serve as interim president. This left the country with two rival administrations and a worsening political crisis. Cassamá quickly resigned on March 1, though, saying that his life had been threatened and citing the risk of civil war. Also in March, military troops were deployed to various government offices and public broadcasting stations, which they temporarily occupied while Nabiam formed a new cabinet. In September the Supreme Court dismissed the PAIGC’s petition and upheld the results of the election; the PAIGC said it accepted the court’s ruling.

The political climate was still tense when an attempted coup occurred on February 1, 2022, during which Embaló and his government were reportedly targeted for assassination. Although the coup ultimately failed, 11 people were killed. It was not immediately clear who was behind the attempt, but Emabaló stated the Bissau-Guinean military was not involved.