The country that began as a king’s private domain (the Congo Free State), evolved into a colony (the Belgian Congo), became independent in 1960 (as the Republic of the Congo), and later underwent several name changes (to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, then to Zaire, and back again to the Democratic Republic of the Congo) is the product of a complex pattern of historical forces. Some are traceable to the precolonial past, others to the era of colonial rule, and others still to the political convulsions that followed in the wake of independence. All, in one way or another, have left their imprint on Congolese societies.

Precolonial perspectives

Before experiencing radical transformations in the colonial era, Congolese societies had already experienced major disruptions. From the 15th to the 17th century several important state systems evolved in the southern savanna region. The most important were the Kongo kingdom in the west and the Luba-Lunda states in the east. They developed elaborate political institutions, buttressed by symbolic kingship and military force. Power emanated from the capital to outlying areas through appointed chiefs or local clan heads. Competition for the kingship often led to civil strife, however, and, with the rise of the slave trade, new sources of instability influenced regional politics. The history of the Kongo peoples in the 16th century, for example, is largely the story of how the Atlantic slave trade created powerful vested interests among provincial chiefs, which over time undermined the kingdom’s capacity to resist encroachments by its neighbors. By the late 16th century the kingdom had all but succumbed to the attacks of the Imbangala (referred to as Jaga in contemporary sources), bands of fighters fleeing famine and drought in the east. Two centuries later fragmentation also undermined political institutions among the Lunda and the Luba, followed by attacks from interlopers eager to control trade in slaves and ivory.

In the tropical rainforest, the radically different ecological conditions raised formidable obstacles to state formation. Small-scale societies, organized into village communities, were the rule. Corporate groups combining social and economic functions among small numbers of related and unrelated people formed the dominant mode of organization. Exchange took place through trade and gift-giving. Over time these social interactions fostered cultural homogeneity among otherwise distinctive communities, such as Bantu and Pygmy groups. Bantu communities absorbed and intermarried with their Pygmy clients, who brought their skills and crafts into the culture. This predominance of house and village organization stands in sharp contrast to the more centralized state structures characteristic of the savanna kingdoms, which were far more adept at acting in a concerted manner than the segmented societies in the tropical rainforest. The segmented nature of the tropical rainforest societies hindered their ability to resist a full-scale invasion by colonial forces.

In the savanna region, resistance to colonial forces was undermined by internecine raids and wars that followed the slave trade, by the increased devastation wrought on African kingdoms when those forces adopted the use of increasingly sophisticated firearms, and by the divisions between those who collaborated with outsiders and those who resisted. The relative ease with which these Congolese societies yielded to European conquest bears testimony to the magnitude of earlier upheavals.

The Congo Free State

King Leopold II of the Belgians set in motion the conquest of the huge domain that was to become his fiefdom. The king’s attention was drawn to the region during British explorer and journalist Henry Morton Stanley’s exploration of the Congo River in 1874–77. In November 1878 Leopold formed the Committee for Studies of the Upper Congo (Comité d’Études du Haut Congo, later renamed Association Internationale du Congo) to open up the African interior to European trade along the Congo River. Between 1879 and 1882, under the committee’s auspices, Stanley established stations in the upper Congo and opened negotiations with local rulers. By 1884 the Association Internationale du Congo had signed treaties with 450 independent African entities and, on that basis, asserted its right to govern all the territory concerned as an independent state.

Leopold’s thinly veiled colonial ambitions paved the way for the Berlin West Africa Conference (1884–85), which set the rules for colonial conquest and sanctioned his control of the Congo River basin area to be known as the Congo Free State (1885–1908). Armed with a private mandate from the international community of the time, and under the guise of his African International Association’s humanitarian mission of ending slavery and bringing religion and the benefits of modern life to the Congolese, Leopold created a coercive instrument of colonial hegemony.

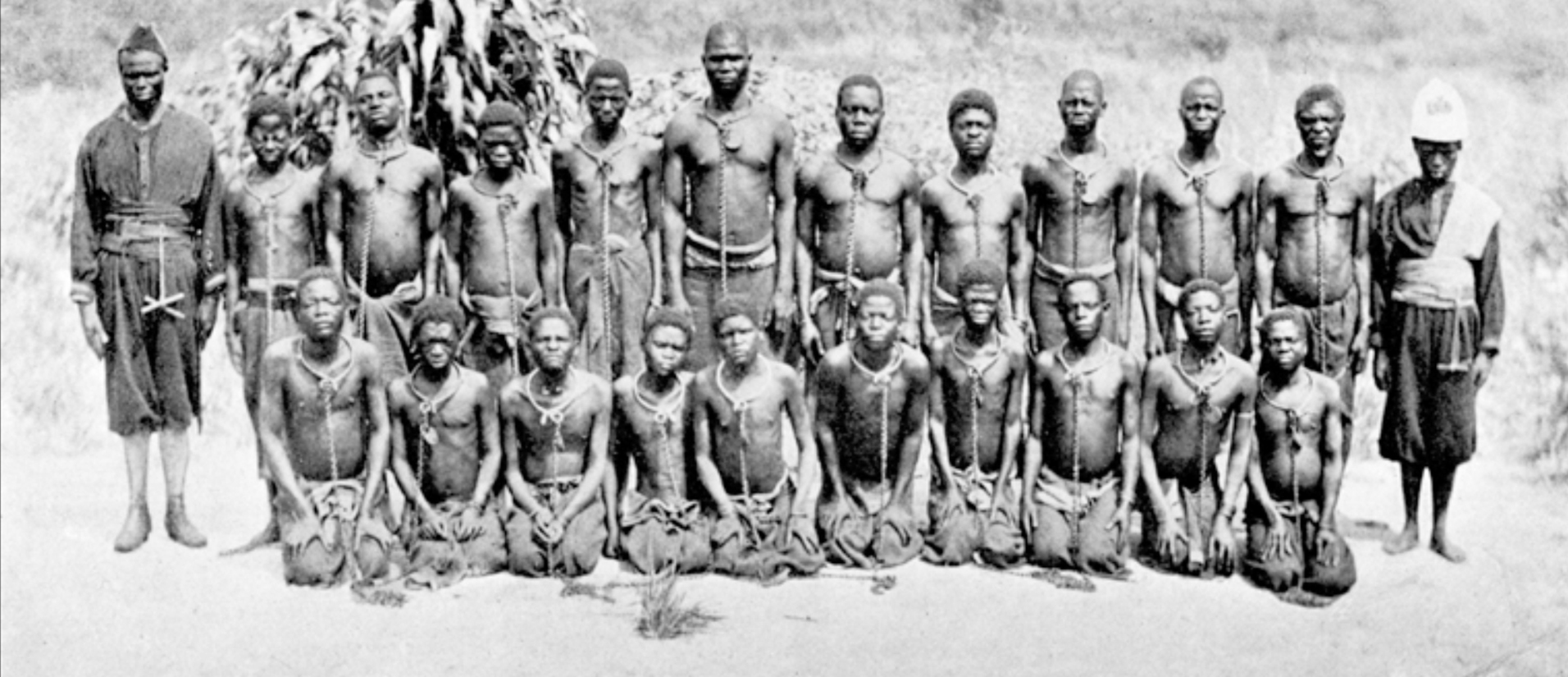

The name Congo Free State is closely identified with the extraordinary hardships and atrocities visited upon the Congolese masses in the name of Leopold’s “civilizing mission.” “Without the railroad,” said Stanley, “the Congo is not worth a penny.” Without recourse to forced labor, however, the railroad could not be built, and the huge concessions that had been made to private European companies would not become profitable, nor could African resistance in the east be overcome without massive recruitment of indigenous troops. The cruel logic of the revenue imperative led Leopold to transform his nascent administrative system into a machine designed to extract not only the maximum amount of natural resources from the land but also the maximum output of labor from the people. To secure the labor necessary to accomplish Leopold’s goals, his agents employed such methods as kidnapping the families of Congolese men, who were forced to meet often unrealistic work quotas to secure their families’ release. Those who tried to rebel were dealt with by Leopold’s private army, the Force Publique—a band of African soldiers led by European officers—who burned the villages and slaughtered the families of rebels. The Force Publique troops were also known for cutting off the hands of the Congolese, including children; the mutilations served to further terrorize the Congolese into submission.

In the wake of intense international criticism prompted by exposés by the American writer Mark Twain, the English journalist E.D. Morel, and various missionaries, in 1908 the Belgian Parliament voted to annex the Congo Free State—essentially purchasing the area from King Leopold and thus placing what was once the king’s holding under Belgian rule. Nevertheless, the destructive impact of the Congo Free State lasted well beyond its brief history. The widespread social disruption not only complicated the establishment of a viable system of administration; it also left a legacy of anti-Western sentiment on which subsequent generations of nationalists were able to capitalize.

Belgian paternalism and the politics of decolonization

The paternalistic tendencies of Belgian colonial rule bore traces of two characteristic features of Leopoldian rule: an irreducible tendency to treat Africans as children and a firm commitment to political control and compulsion. The elimination of the more brutal aspects of the Congo Free State notwithstanding, Belgian rule remained conspicuously unreceptive to political reform. By placing the inculcation of Western moral principles above political education and apprenticeship for social responsibility, Belgian policies virtually ruled out initiatives designed to foster political experience and responsibility.

Not until 1957, with the introduction of a major local government reform (the so-called statut des villes [“statute of the cities”]), were Africans afforded a taste of democracy. By then a class of Westernized Africans (évolués), eager to exercise their political rights beyond the urban arenas, had arisen. Moreover, heavy demands made upon the rural masses during the two world wars, coupled with the profound psychological impact of postwar constitutional reforms introduced in neighbouring French-speaking territories, created a climate of social unrest suited for the development of nationalist sentiment and activity.

The publication in 1956 of a political manifesto calling for immediate independence precipitated the political awakening of the Congolese population. Penned by a group of Bakongo évolués affiliated with the Alliance des Bakongo (ABAKO), an association based in Léopoldville (now Kinshasa), the manifesto was the response of ABAKO to the ideas set forth by a young Belgian professor of colonial legislation, A.A.J. van Bilsen, in his “Thirty-Year Plan for the Political Emancipation of Belgian Africa.” Far more impatient than its catalyst, the ABAKO manifesto stated: “Rather than postponing emancipation for another thirty years, we should be granted self-government today.”

Under the leadership of Joseph Kasavubu, ABAKO transformed itself into a vehicle of anticolonial protest. Nationalist sentiment spread through the lower Congo region, and, in time, the nationalist wave washed over the rest of the colony. Self-styled nationalist movements appeared almost overnight in every province. Among the welter of political parties brought into existence by the statut des villes, the Congolese National Movement (Mouvement National Congolais; MNC) stood out as the most powerful force for Congolese nationalism. The MNC never disavowed its commitment to national unity (unlike ABAKO, whose appeal was limited to Bakongo elements), and with the arrival of Patrice Lumumba—a powerful orator, advocate of pan-Africanism, and cofounder of the MNC—in Léopoldville in 1958 the party entered a militant phase.

The turning point in the process of decolonization came on January 4, 1959, when anti-European rioting erupted in Léopoldville, resulting in the death of scores of Africans at the hands of the security forces. On January 13 the Belgian government formally recognized independence as the ultimate goal of its policies—a goal to be reached “without fatal procrastination, yet without fatal haste.” By then, however, nationalist agitation had reached a level of intensity that made it virtually impossible for the colonial administration to control the course of events. The Belgian government responded to this growing turbulence by inviting a broad spectrum of nationalist organizations to a Round Table Conference in Brussels in January 1960. The aim was to work out the conditions of a viable transfer of power; the result was an experiment in instant decolonization. Six months later, on June 30, the Congo formally acceded to independence and quickly descended into chaos.

The Congo crisis

The triggering events behind the “Congo crisis” were the mutiny of the army (the Force Publique) near Léopoldville on July 5 and the subsequent intervention of Belgian paratroopers, ostensibly to protect the lives of Belgian citizens.

Adding to the confusion was a constitutional impasse that pitted the new country’s president and prime minister against each other and brought the Congolese government to a halt. In the Congo’s first national elections, Lumumba’s MNC party had outpolled Kasavubu’s ABAKO and its allies, but neither side could form a parliamentary coalition. As a compromise measure, Kasavubu and Lumumba formed an uneasy partnership with the former as president and the latter as premier. On September 5, however, Kasavubu relieved Lumumba of his functions, and Lumumba responded by dismissing Kasavubu; as a result of the discord, there were two groups now claiming to be the legal central government.

Meanwhile, on July 11, the country’s richest province, Katanga, declared itself independent under the leadership of Moise Tshombe. The support given by Belgium to the Katanga secession lent credibility to Lumumba’s claims that Brussels was trying to reimpose its authority, and on July 12 he and Kasavubu appealed to United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld for UN security assistance. While intended to pave the way for the restoration of peace and order, the arrival of the UN peacekeeping force added to the tension between President Kasavubu and Prime Minister Lumumba. Lumumba’s insistence that the UN should, if necessary, use force to bring Katanga back under control of the central government met with categorical opposition from Kasavubu. Lumumba then appealed to the Soviet Union for logistical assistance to send troops to Katanga. At that point, the Congo crisis became inextricably bound up with East-West animosities in the context of the Cold War.

As the process of fragmentation set in motion by the Katanga secession reached its peak, resulting in the breakup of the country into four separate fragments (Katanga, Kasai, Orientale province, and Léopoldville), army Chief of Staff Joseph Mobutu (later Mobutu Sese Seko) took power in a coup d’état: he announced on September 14, 1960, that the army would henceforth rule with the help of a caretaker government. The threat posed to the new regime by the forces loyal to Lumumba was substantially lessened by the capture of Lumumba in December 1960, after a dramatic escape from Léopoldville the previous month (see Patrice Lumumba), and by his subsequent execution at the hands of the Tshombe government. Although Kasavubu had Lumumba arrested and delivered to the Katanga secessionists, which was intended to pave the way for a reintegration of the province, it was not until January 1963—and only after a violent showdown between the European-trained Katanga gendarmerie and the UN forces—that the secession was decisively crushed. Another secession challenge emerged on September 7, 1964, when the pro-Lumumba government in Stanleyville (Kisangani) declared much of eastern Congo to be the People’s Republic of the Congo; this secession was brought to heel the next year. Meanwhile, following the convening of the parliament in Léopoldville, a new civilian government headed by Cyrille Adoula came to power on August 2, 1961.

Adoula’s inability to deal effectively with the Katanga secession and his decision to dissolve the parliament in September 1963 critically undermined his popularity. The dissolution of the parliament contributed directly to the outbreak of rural insurgencies, which engulfed 5 of 21 provinces between January and August 1964, and raised again the prospect of a total collapse of the central government. Because of its poor leadership and fragmented bases of support, however, the rebellion failed to translate its early military successes into effective political power; even more important in turning the tide against the insurgents was decisive intervention by European mercenaries, who helped the central government regain control over rebel-held areas. Much of the credit for the survival of the government goes to Tshombe, who by July 10, 1964, had replaced Adoula as prime minister. Ironically, then, a year and a half after his defeat at the hands of the UN forces, Tshombe, the most vocal advocate of secession, had emerged as the providential leader of a besieged central government.

Mobutu’s regime

Mobutu’s second coup, on November 24, 1965, occurred in circumstances strikingly similar to those that had led to the first—a struggle for power between the incumbent president, Kasavubu, and his prime minister, this time Tshombe. Mobutu’s coup saw to the removal of Kasavubu and Tshombe, and Mobutu himself proceeded to assume the presidency. Unlike Lumumba, however, Tshombe managed to leave the country unharmed—and determined to regain power. Rumours that the ousted prime minister was plotting a comeback from exile in Spain hardened into certainty when in July 1966 some 2,000 of Tshombe’s former Katanga gendarmes, led by mercenaries, mutinied in Kisangani. Exactly one year after the crushing of that first mutiny, a second broke out, again in Kisangani, apparently triggered by the news that Tshombe’s airplane had been hijacked over the Mediterranean and forced to land in Algiers, where he was then held prisoner and later died of a heart attack. Led by a Belgian settler named Jean Schramme and including approximately 100 former Katanga gendarmes and about 1,000 Katangese, the mutineers held their ground against the 32,000-man Congolese National Army (Armée Nationale Congolaise; ANC) until November 1967, when the mercenaries crossed the border into Rwanda and surrendered to the local authorities. Schramme himself later turned up in Brazil, where he remained in spite of attempts by the Belgian government to have him extradited.

The country settled into a semblance of political stability for the next several years, allowing Mobutu to focus on his unsuccessful strategies for economic progress. In 1971 Mobutu renamed the country Zaire as part of his “authenticity” campaign—his effort to emphasize the country’s cultural identity. Officially described as “the nation politically organized,” Mobutu’s MPR, the sole political party from 1970 to 1990, may be better seen as a weakly articulated patronage system. Mobutu’s effort to extol the virtues of Zairian “authenticity” did little to lend respectability either to the concept or to the brand of leadership for which it stood. As befit his chiefly image, Mobutu’s rule was based on bonds of personal loyalty between himself and his entourage.

The fragility of Mobutu’s power base was demonstrated in 1977 and ’78, when the country’s main opposition movement, the Congolese National Liberation Front (Front de la Libération Nationale Congolaise; FLNC), operating from Angola, launched two major invasions into Shaba (which Katanga was called from 1972 to 1997). On both occasions external intervention by friendly governments—primarily Morocco in 1977 and France in 1978—saved the day, but at the price of many African and European casualties. Shortly after the capture of the urban centre of Kolwezi by the FLNC in May 1978, an estimated 100 Europeans lost their lives at the hands of the rebels and the ANC. Apart from the role played by the FLNC in spearheading the invasions, the sharp deterioration of the Zairian economy after 1975, coupled with the rapid growth of anti-Mobutu sentiment among the poor and the unemployed, was a crucial factor in the near success of the invasions of Shaba. The timing of the first Shaba invasion, a full 11 years after the creation of the Popular Movement of the Revolution (Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution; MPR) in 1966, underscored the shortcomings of the single-party state as a vehicle for national integration and of “Mobutism” as an ideology for the legitimization of Mobutu’s regime.

Circumstances changed dramatically with the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s. Former supporters on the international scene, such as the United States, France, and Belgium, pressed for democratic reforms; some even openly supported Mobutu’s rivals. In April 1990 Mobutu did decide to lift the ban on opposition parties, but he followed that liberalizing act with the brutal repression of student protests at the University of Lubumbashi in May—resulting in the death of 50 to 150 students, according to Amnesty International. In 1991 France reduced its monetary aid to the country, U.S. diplomats criticized Mobutu before the U.S. Congress, and the World Bank cut ties with Mobutu following his appropriation of $400 million from Gécamines, the state mining corporation.

Mobutu grudgingly agreed to relinquish some power in 1991: he convened a national conference that resulted in the formation of a coalition group, the High Council of the Republic (Haut Conseil de la République; HCR), a provisional body charged with overseeing the country’s transfer to a multiparty democracy. The HCR selected Étienne Tshisekedi as prime minister. Tshisekedi, an ethnic Luba from the diamond-rich Kasaï-Oriental province, was known as a dissident as early as 1980, when he and a small group of parliamentarians charged the army with having massacred some 300 diamond miners. Tshisekedi’s renewed prominence highlighted the key role that natural resources continued to play in national politics.

Meanwhile, Mobutu, resistant to the transfer of authority to Tshisekedi, maneuvered to pit groups within the HCR against each another. He also ensured the support of military units by giving them the right to plunder whole regions of the country and certain sectors of the economy. Eventually these maneuvers undermined Tshisekedi and resuscitated the regime; Mobutu reached an agreement with the opposition, and Kengo wa Dondo became prime minister in 1994. Mobutu agreed to government reforms set forth in the Transitional Constitutional Act (1994), but real reforms and promised elections never took place.

The Rwandan crisis of 1993–94—rooted in long-running tensions between that country’s two major ethnic groups, the Hutu and the Tutsi—and the ensuing genocide (during which more than 800,000 civilians, primarily Tutsi, were killed) afforded Mobutu an opportunity to mend his relationships with the Western powers. Following the late-1993 invasion of Rwanda by the forces of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a Tutsi-led Rwandan exile organization, Mobutu offered logistical and military support to the French and Belgian troops who intervened to support the Hutu-led Rwandan government. This move renewed relations with France and ultimately led Belgium and the United States to reopen diplomatic channels with Mobutu. Business ventures that promised foreign firms privileged access to the country’s resources and state enterprises further bolstered external support.

Mobutu also encouraged attacks against Zairians of Rwandan Tutsi origin living in the eastern part of the country; this was one of the maneuvers that ultimately sowed the seeds of his downfall. The attacks, coupled with Mobutu’s support of a faction of Hutu (exiled in Zaire) who opposed the Rwandan government, ultimately led local Tutsi and the government of Rwanda to join forces with Mobutu’s opponent Laurent Kabila and his Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo-Zaïre; AFDL). Kabila’s opposition forces also gained the backing of the governments of Angola and Uganda, as Mobutu had supported rebel movements within those countries. (Mobutu’s associates had engaged in diamond trafficking with National Union for the Total Independence of Angola [UNITA] rebels; Mobutu also had allowed supplies for Ugandan rebels to be transported via a Zairian airport.)

In October 1996, while Mobutu was abroad for cancer treatment, Kabila and his supporters launched an offensive from bases in the east and subsequently captured Bukavu and Goma, a city on the shore of Lake Kivu. Mobutu returned to the country in December but failed to stabilize the situation. The rebels continued to advance, and on March 15, 1997, Kisangani fell, followed by Mbuji-Mayi and Lubumbashi in early April. South African-backed negotiations between Mobutu and Kabila in early May quickly failed, and the victorious forces of the AFDL entered the capital on May 17, 1997. By this time, Mobutu had fled. He died in exile a few months later.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo

Following Mobutu’s departure, Kabila assumed the presidency and restored the country’s previous name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Kabila initially was able to attract foreign aid and provided some order and relief to the country’s decimated economy. He also initiated the drafting of a new constitution. The outward appearance of moving toward democracy conflicted with the reality of the situation: Kabila held the bulk of power and did not tolerate criticism or opposition. Political parties and public demonstrations were banned almost immediately following Kabila’s takeover of the government, and his administration was accused of human rights abuse.

In August 1998 the new leader himself was plagued by a rebellion in the country’s eastern provinces—supported by some of Kabila’s former allies. The rebellion marked the start of what became a devastating five-year civil war that drew in several countries. By the end of 1998, the rebels, backed by the Ugandan and Rwandan governments, controlled roughly one-third of the country. Kabila’s government received support from the Angolan, Namibian, and Zimbabwean governments in its fight against the rebels. A cease-fire and the deployment of UN peacekeeping forces were among the provisions of the 1999 Lusaka Peace Accord, an agreement intended to end the hostilities. Although it was eventually signed by most parties involved in the conflict, the accord was not fully implemented, and fighting continued. Meanwhile, long-standing ethnic tensions between the Hema and the Lendu peoples erupted into violence in the Ituri district in the eastern part of the country; this was further complicated by rebel involvement and other political and economic factors, spawning an additional conflict in a region already mired in the civil war.

Kabila was assassinated in January 2001. He was succeeded by his son, Joseph, who immediately declared his commitment to finding a peaceful end to the war. Soon after Joseph Kabila assumed power, the Rwandan and Ugandan governments and the rebels agreed to a UN-proposed pull-out plan, but it was never fully actualized. Finally, in December 2002, an agreement reached in Pretoria, South Africa, provided for the establishment of a power-sharing transitional government and an end to the war; this agreement was ratified in April 2003. A transitional constitution also was adopted that month and an interim government was inaugurated in July, with Kabila as president. UN peacekeeping troops continued to maintain a presence in the country.

Although the civil war was technically over, the country was devastated. It was estimated that more than three million people had been killed; those who survived were left to struggle with homelessness, starvation, and disease. The new government was fragile; the economy was in shambles; and societal infrastructure had been destroyed. With international assistance, Kabila was able to make considerable progress toward reforming the economy and began the work of rebuilding the country. However, his government was not able to exercise any real control over much of the country; he had to cope with fighting that remained in the east, as well as two failed coup attempts in 2004. Nevertheless, a new, formal constitution was promulgated in 2006, and Kabila was victorious in presidential elections held later that year.

In January 2008 a peace agreement aimed at ending the fighting in the eastern part of the country was signed by the government and more than 20 rebel groups. The fragile truce was broken later that year when rebels led by Laurent Nkunda renewed their attacks, displacing tens of thousands of residents and international aid workers. In January 2009 Congolese and Rwandan troops together launched an offensive against rebel groups in the east. They forced Nkunda to flee across the border into Rwanda, where he was arrested and indicted for war crimes by the Congolese government. In May 2009 further efforts to resolve the continuing conflict in the east included an amnesty extended to several militant groups there. Still, violence in the east persisted, casting a pall on the celebrations of the country’s 50th anniversary of independence in 2010.

The country held presidential and parliamentary elections in November 2011. Eleven candidates stood in the presidential race, with Kabila and former prime minister Étienne Tshisekedi being the front-runners. A January 2011 constitutional amendment had eliminated the second round of voting in the presidential race, allowing for the possibility that a candidate might win the presidency without the support of the majority of voters, a change that many thought bolstered Kabila’s chances of reelection. Despite problems with distributing electoral supplies to the country’s many remote polling centers, the elections were held as scheduled on November 28. The tallying of parliamentary results was expected to take several weeks, while the tabulation of the presidential votes was expected to be completed in a week, although it took slightly longer, as the process was hindered by the same logistical obstacles that complicated the distribution of electoral supplies. After two short delays in the release of the provisional results, Kabila was declared the winner, with 49 percent of the vote; Tshisekedi followed, with 32 percent. The Supreme Court later confirmed the results, although several international monitoring groups characterized the polls as being poorly organized and noted many irregularities. Tshisekedi’s party rejected the results, and he declared himself to be Congo’s rightful president; to that end, he had himself sworn in as president on December 23, three days after Kabila’s official inauguration had taken place. The tallying of the parliamentary election results also took longer than expected. Results released in late January and early February 2012 showed that more than 100 parties would be represented in the National Assembly and that no one party had won a majority. Kabila’s party and its allies, however, together had won slightly more than half of the 500 seats.

With Kabila’s presidential mandate set to expire at the end of 2016, there were fears evident as early as 2013 that he would find a way to extend his time in office, whether by modifying the constitution or by finding a reason to postpone the next presidential election, and, fueled by such fears, many protests were held. In 2015 Kabila’s administration proposed a series of actions to precede the next elections, including conducting a census, reorganizing the country’s administrative units (which would more than double the number of provinces), and overhauling the voter registry, a task expected to take more than a year to complete. Many thought that these actions would delay the elections and ultimately extend Kabila’s term in office by several years. Further stoking suspicions that he would not step down as scheduled, in May 2016 the Constitutional Court ruled that if the polls were delayed, Kabila could remain in office until a successor was elected. In September the electoral commission formally requested that the Constitutional Court allow for the 2016 presidential election to be postponed; the court ruled in favor of the request the following month, which angered the opposition. A crisis appeared to be averted, however, when a hard-wrought compromise deal was signed by the government and most opposition groups on December 31. Its provisions included allowing Kabila to remain president, but of a transitional government with a prime minister selected from the opposition, until a new president could be elected in 2017.

To the consternation of many, the presidential election did not occur as planned; it was eventually scheduled to take place on December 23, 2018, along with legislative, provincial, and local elections. In August 2018 Kabila’s spokesperson confirmed that Kabila would not be standing in the presidential election. Instead, the candidate of the ruling party (the People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy; PPRD) would be Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, a former government minister and provincial governor. Shadary was one of 21 approved presidential candidates. Notable opposition figures Jean-Pierre Bemba and Moïse Katumbi were not part of that group, as Bemba had been disqualified by the electoral commission over International Criminal Court charges and Katumbi had been blocked from returning to the country after time away and hence was not able to register as a candidate by the deadline. Although the opposition groups initially united to back Martin Fayulu as their candidate, protests from supporters of Félix Tshisekedi—son of veteran opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi, who had died in 2017—led him to withdraw his support from Fayulu and contest the election himself. Another opposition leader with broad support, Vital Kamerhe, did the same.

Tensions increased in the run-up to the elections, as evidenced by the violence committed by security forces at political rallies and by the decision of Kinshasa’s governor to ban campaign events in the city days before the scheduled polls. Ten days before the elections were to be held, a mysterious fire destroyed thousands of voting machines and other election materials in Kinshasa, an opposition stronghold. Against this backdrop, there were concerns that peaceful, free, and fair elections could not be held throughout the country. Indeed, just three days before the scheduled date of the elections, the electoral commission announced that it could not hold the elections as planned and hence was postponing them until December 30. Shortly thereafter the electoral commission announced that voting would be postponed until March in and around three cities—Beni, Butembo, and Yumbi, all opposition strongholds—citing regional insecurity and an outbreak of the Ebola virus disease as reasons for the delay. Given that the next president was scheduled to be inaugurated in January, the postponement effectively discounted the votes of the electorate in those areas, which represented about 3 percent of all registered voters..

Elections did take place on December 30 in the rest of the country. Although the voting day was generally peaceful, there were complaints about the process, including those about polling stations not opening on time or lacking necessary supplies, as well as instances of voter intimidation and monitors being denied access to polling stations and, later, vote-counting centres. When results were released on January 10, Tshisekedi was announced the winner, with more than 38 percent of the vote; he was trailed by Fayulu, with almost 35 percent, and Shadary, with almost 24 percent. The results, however, were counter to a preelection poll and the observations of Congo’s Catholic bishops organization (National Episcopal Conference of Congo; CENCO) election monitoring group, both of which had Fayulu firmly in the lead. Fayulu and others alleged that Tshisekedi and Kabila had made a deal: an election victory for Tshisekedi in exchange for Kabila and his associates having their interests protected. Representatives of Kabila and Tshisekedi denied the accusation.

Fayulu challenged the results with the Constitutional Court. His argument was bolstered by a trove of leaked election data as well as the results compiled by CENCO, both of which showed him winning about 60 percent of the vote. The court upheld Tshisekedi’s victory, however, and he was sworn in as president on January 24, 2019. Against the backdrop of lingering questions about the credibility of the election results, the day was still significant, as Tshisekedi’s inauguration was the first peaceful transfer of power in Congo since the country became independent in 1960.