Idi Amin: Early Life and Military Career

Idi Amin Dada was born c. 1925 in Koboko, in northwestern Uganda, to a Kakwa father and Lugbara mother, who separated shortly afterward. In 1946, after receiving only a rudimentary education, Amin joined the King’s African Rifles (KAR), a regiment of the British colonial army, and quickly rose through the ranks. He was deployed to Somalia in 1949 to fight the Shifta rebels and later fought with the British during the suppression of the Mau Mau Rebellion in Kenya (1952-56). In 1959 he attained the rank of effendi—the highest position for a black African soldier within the KAR—and, by 1966, he had been appointed commander of the armed forces.

Did you know? During his time in the army, Amin became the light heavyweight boxing champion of Uganda, a title he held for nine years between 1951 and 1960.

Amin Commandeers Control of Uganda’s Government

After more than 70 years under British rule, Uganda gained its independence on October 9, 1962, and Milton Obote became the nation’s first prime minister. By 1964, Obote had forged an alliance with Amin, who helped expand the size and power of the Ugandan Army. In February 1966, following accusations that the pair was responsible for smuggling gold and ivory from Congo that was subsequently traded for arms, Obote suspended the constitution and proclaimed himself executive president. Shortly thereafter, Obote sent Amin to dethrone King Mutesa II, also known as “King Freddie,” who ruled the powerful kingdom of Buganda in south-central Uganda.

A few years and two failed—but unidentified—assassination attempts later, Obote began to question Amin’s loyalty and ordered his arrest while en route to Singapore for a Commonwealth Heads of Government Conference. During his absence, Amin took the offensive and staged a coup on January 25, 1971, seizing control of the government and forcing Obote into exile.

Amin’s Regime

Once in power, Amin began mass executions upon the Acholi and Lango, Christian tribes that had been loyal to Obote and therefore perceived as a threat. He also began terrorizing the general public through the various internal security forces he organized, such as the State Research Bureau (SRB) and Public Safety Unity (PSU), whose main purpose was to eliminate those who opposed his regime.

In 1972, Amin expelled Uganda’s Asian population, which numbered between 50,000 and 70,000, resulting in a collapse of the economy as manufacturing, agriculture, and commerce came to a screeching halt without the appropriate resources to support them.

When the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) hijacked an Air France flight from Israel to Paris on June 27, 1976, Idi Amin welcomed the terrorists and supplied them with troops and weapons, but was humiliated when Israeli commandos subsequently rescued the hostages in a surprise raid on the Entebbe airport. In the aftermath, Amin ordered the execution of several airport personnel, hundreds of Kenyans who were believed to have conspired with Israel, and an elderly British hostage who had previously been escorted to a nearby hospital.

Throughout his oppressive rule, Amin was estimated to have been responsible for the deaths of roughly 300,000 civilians.

Amin Loses Control and Enters Exile

Over time, the number of Amin’s intimate allies dwindled and formerly loyal troops began to mutiny. When some fled across the border into Tanzania, Amin accused Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere of instigating the unrest and retaliated by annexing the Kagera Salient, a strip of territory north of the Kagera River, in November 1978. Two weeks later, Nyerere mobilized a counter-offensive to recapture the land and drove the Ugandan Army out with the help of Ugandan exiles. The battle raged into Uganda, and on April 11, 1979, Amin was forced to flee when Kampala was captured. Although he originally sought refuge in Libya, he later moved to Saudi Arabia, where he lived comfortably until his death of multiple organ failure in 2003.

Early Life

Idi Amin Dada Oumee was born around 1923 near Koboko, in the West Nile Province of what is now the Republic of Uganda. Deserted by his father at an early age, he was brought up by his mother, an herbalist, and diviner. Amin was a member of the Kakwa ethnic group, a small Islamic tribe that had settled in the region.

Success in the King's African Rifles

Amin received little formal education. In 1946, he joined Britain's colonial African troops known as the King's African Rifles (KAR) and served in Burma, Somalia, Kenya (during the British suppression of the Mau Mau), and Uganda. Although he was considered a skilled soldier, Amin developed a reputation for cruelty and was almost cashiered on several occasions for excessive brutality during interrogations. Nevertheless, he rose through the ranks, reaching sergeant major before finally being made an effendi, the highest rank possible for a Black African serving in the British army. Amin was also an accomplished athlete, holding Uganda's light heavyweight boxing championship title from 1951 to 1960.

A Violent Start

As Uganda approached independence, Amin's close colleague Apollo Milton Obote, the leader of the Uganda People's Congress (UPC), was made chief minister and then prime minister. Obote had Amin, one of only two high-ranking Africans in the KAR, appointed as first lieutenant of the Ugandan Army. Sent north to quell cattle stealing, Amin perpetrated such atrocities that the British government demanded he be prosecuted. Instead, Obote arranged for him to receive further military training in the U.K.

Soldier for the State

On his return to Uganda in 1964, Amin was promoted to major and given the task of dealing with an army in mutiny. His success led to a further promotion to colonel. In 1965, Obote and Amin were implicated in a deal to smuggle gold, coffee, and ivory out of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. A parliamentary investigation demanded by President Edward Mutebi Mutesa II put Obote on the defensive. Obote promoted Amin to general and made him chief-of-staff, had five ministers arrested, suspended the 1962 constitution, and declared himself president. Mutesa was forced into exile in 1966 after government forces, under the command of Amin, stormed the royal palace.

Coup d'Etat

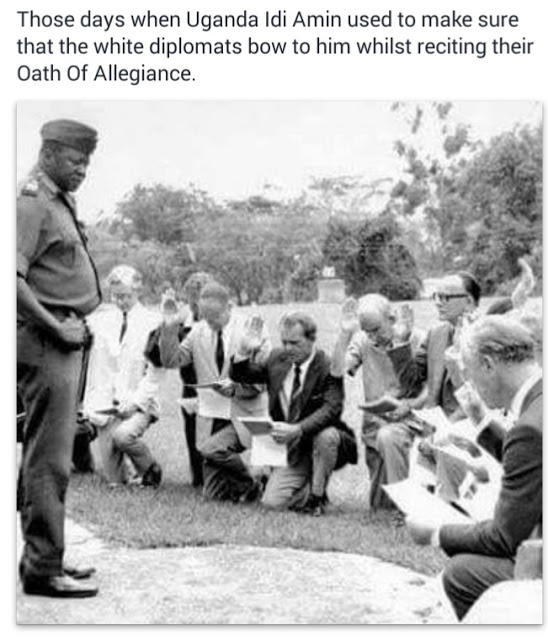

Idi Amin began to strengthen his position within the Army using the funds obtained from smuggling and from supplying arms to rebels in southern Sudan. He also developed ties with British and Israeli agents in the country. President Obote first responded by putting Amin under house arrest. When this failed to work, Amin was sidelined to a non-executive position in the Army. On January 25, 1971, while Obote was attending a meeting in Singapore, Amin led a coup d'etat, taking control of the country and declaring himself president. Popular history recalls Amin's declared title to be "His Excellency President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Idi Amin, VC, DSO, MC, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Sea, and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular."

Amin was initially welcomed both within Uganda and by the international community. President Mutesa—fondly known as "King Freddie"—had died in exile in 1969, and one of Amin's earliest acts was to have the body returned to Uganda for a state burial. Political prisoners (many of whom were Amin followers) were freed and the Ugandan Secret Police was disbanded. At the same time, however, Amin formed "killer squads" to hunt down Obote's supporters.

The Asians and Idi Amin

By the late 1960s it is clear that the Black Spot had been placed on the Asian minority of East Africa. Once regarded as an asset to these countries, they had been redefined as a problem not just by African nationalist rulers, but by many Western intellectuals as well. As Paul Theroux noted in his 1967 essay "Hating the Asians", the vulnerable position of this minority was "the result of a collaboration, most likely unthought-out and maybe even unconscious, between outsiders and insiders; almost a conspiracy of Africans and their European apologists, who would very much like to see Africa succeed, even at the expense of a pogrom, a thorough purge of these immigrant peoples."

In February 1968 Ugandan President Milton Obote had warned that "We will keep non-Ugandan citizens at our pleasure but if, for national interests, that pleasure runs out, they will have to go to their countries." In a despatch dated February 24 1970 The Times of London wrote of the growing fears of Asian non-citizens in Uganda. This was the consequence of the Ugandan Immigration Act, flagged in the cabinet memorandum mentioned above, that was due to go into effect on May 1. According to the report Asians feared that the requirement for permits "for non-citizens to hold jobs or own shops will force them out of the country."

The newspaper reported that the Asians were already subject to severe discrimination with Asian traders "barred by the Government in trading in 34 commodities, including everyday items such as groceries." It also observed that "Asians in Uganda form most of the middle class, as they do in Kenya. But there is one difference: there was already the core of an African middle class here when Uganda became independent. Therefore the ‘Africanisation' process is expected to be applied more systematically than it has been in Kenya. There is a schedule for ousting, district-by-district, all non-Ugandan citizens."

These fears were not immediately realized and in January 1971 Milton Obote was ousted in a coup d'état by General Idi Amin. The New York Times reported, on January 31 1972, that having put a halt to Obote's "move-to-the-left" programmed the Ugandan economy appeared to be heading out of serious economic trouble. It did note however that while nationalization had been put on hold the government was putting greater emphasis on "Ugandisation of industry and retail and wholesale trade, which now is largely in the hands of the country's more than 80 000 Asians."

By 1972 it was government policy in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania that all Asian United Kingdom passport holders would have to leave eventually. As a British cabinet memorandum on the "Asian Problem in East and Central Africa" (December 1972) noted, the Asians "are unpopular". The "degree of resentment varies... but the reasons are broadly speaking the same. It is not just that they have attained a controlling position in trade, disproportionate to their numbers, but they constitute an important middle class element, holding jobs in management, teaching and the civil service, to which the new newly-educated Africans aspire."

The governments of Kenya and Tanzania were willing to pursue this goal gradually but purposefully - with Kenya, in particular, mindful of the need to avoid too much economic disruption. Idi Amin, who had only reached grade 4 in school, would prove less susceptible to considerations of economic rationality and traditional British diplomatic cajoling.

On August 4 Idi Amin told a contingent of troops that there was "no room" in Uganda for the Asians because they were "economic saboteurs." The following day he announced that Asians with British passports would have to leave Uganda within three months. In a national broadcast Amin said that he would be summoning the British High Commissioner to ask him to "make arrangements and remove the 80 000 British passport holders [this was an overestimate] within three months." He repeated his accusation that the Asians were sabotaging the economy and complained that in most main towns "almost the entire commercial section remained in the hands of Asians. ‘Why have Ugandans not taken over such businesses?' he asked." Amin would say, a short while after, that the decision had come to him after he had had a "dream that the Asian problem was becoming extremely explosive."

The response by the British government was to acknowledge a "special responsibility" to Uganda's non-citizen Asians but to resist their wholesale expulsion from the country. The British Home Secretary, Robert Carr, said a group of ministers and officials had been established to "make sure all action is taken to try and avert the terrible threat overhanging these people." Amin nonetheless reaffirmed his decision stating, on April 9, that any Asians not exempt from his order who overstayed would "be sitting in the fire.

Ethnic Purging

Obote took refuge in Tanzania, from where, in 1972, he attempted unsuccessfully to regain the country through a military coup. Obote supporters within the Ugandan Army, predominantly from the Acholi and Lango ethnic groups, were also involved in the coup. Amin responded by bombing Tanzanian towns and purging the Army of Acholi and Lango officers. The ethnic violence grew to include the whole of the Army, and then Ugandan civilians, as Amin became increasingly paranoid. The Nile Mansions Hotel in Kampala became infamous as Amin's interrogation and torture center, and Amin is said to have moved residences regularly to avoid assassination attempts. His killer squads, under the official titles of "State Research Bureau" and "Public Safety Unit," were responsible for tens of thousands of abductions and murders. Amin personally ordered the execution of the Anglican Archbishop of Uganda, the chancellor of Makerere College, the governor of the Bank of Uganda, and several of his own parliamentary ministers.

Economic War

In 1972, Amin declared "economic war" on Uganda's Asian population, a group that dominated Uganda's trade and manufacturing sectors as well as a significant portion of the civil service. Seventy thousand Asian holders of British passports were given three months to leave the country, and the abandoned businesses were handed over to Amin's supporters. Amin severed diplomatic ties with Britain and "nationalized" 85 British-owned businesses. He also expelled Israeli military advisors, turning instead to Colonel Muammar Muhammad al-Gadhafi of Libya and the Soviet Union for support.

Leadership

Amin was considered by many to be a gregarious, charismatic leader, and he was often portrayed by the international press as a popular figure. In 1975, he was elected chair of the Organisation of African Unity (though Julius Kambarage Nyerere, president of Tanzania, Kenneth David Kaunda, president of Zambia, and Seretse Khama, president of Botswana, boycotted the meeting). A United Nations condemnation was blocked by African heads of state.

Hypomania

Popular legend claims that Amin was involved in blood rituals and cannibalism. More authoritative sources suggest he may have suffered from hypomania, a form of manic depression characterized by irrational behavior and emotional outbursts. As his paranoia became more pronounced, Amin imported troops from Sudan and Zaire. Eventually, less than 25 percent of the Army was Ugandan. Support for his regime faltered as accounts of Amin's atrocities reached the international press. The Ugandan economy suffered, with inflation eclipsing 1,000%.

Exile

In October 1978, with the assistance of Libyan troops, Amin attempted to annex Kagera, the northern province of Tanzania (which shares a border with Uganda). Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere responded by sending troops into Uganda, and with the aid of rebel Ugandan forces they were able to capture the Ugandan capital of Kampala. Amin fled to Libya, where he stayed for almost 10 years before finally relocating to Saudi Arabia. He remained there in exile for the remainder of his life.

Death

On August 16, 2003, Amin died in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The cause of death was reported as multiple organ failure. Although the Ugandan government announced that his body could be buried in Uganda, he was quickly buried in Saudi Arabia. Amin was never tried for his gross abuse of human rights.

Legacy

Amin's brutal reign has been the subject of numerous books, documentaries, and dramatic films, including "Ghosts of Kampala," "The Last King of Scotland," and "General Idi Amin Dada: A Self Portrait." Often depicted in his time as an eccentric buffoon with delusions of grandeur, Amin is now considered one of history's cruelest dictators. Historians believe his regime was responsible for at least 100,000 deaths and possibly many more.