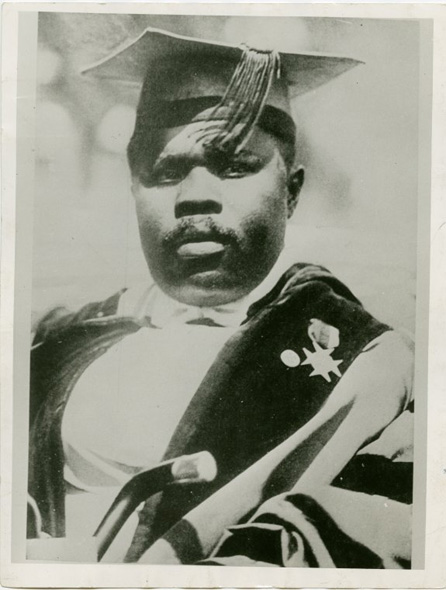

Marcus Moziah Garvey was a charismatic Black leader who organized the first important American Black nationalist movement (1919–26), based in New York City’s Harlem.

He was born August 17, 1887, in St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica—died June 10, 1940, in London, England.

Garvey attended school in Jamaica until he was 14. After traveling in Central America and living in London from 1912 to 1914, he returned to Jamaica, where, with a group of friends, he founded the Universal Negro Improvement and Conservation Association and African Communities League on August 1, 1914, usually called the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), which sought, among other things, to build in Africa a Black-governed nation.

Failing to attract a following in Jamaica, Garvey went to the United States in 1916 and soon established branches of the UNIA in Harlem and the other principal ghettos of the North. By 1919 the rising “Black Moses” claimed a following of about 2,000,000, though the exact number of association members was never clear. From the platform of the Association’s Liberty Hall in Harlem, he spoke of a “New Negro,” proud of being Black. His newspaper, Negro World, told of the exploits of heroes of the race and of the splendors of African culture. He taught that Blacks would be respected only when they were economically strong, and he preached an independent Black economy within the framework of white capitalism. To forward these ends, he established the Negro Factories Corporation and the Black Star Line in 1919, as well as a chain of restaurants and grocery stores, laundries, a hotel, and a printing press.

He reached the height of his power in 1920, when he presided at an international convention in Liberty Hall, with delegates present from 25 countries. The affair was climaxed by a parade of 50,000 through the streets of Harlem, led by Garvey in the flamboyant array.

His slipshod business methods, however, and his doctrine of racial purity and separatism (he even approved of the white racist Ku Klux Klan because it sought to separate the races) brought him bitter enemies among established Black leaders, including labor leader A. Philip Randolph and W.E.B. Du Bois, head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Garvey’s influence declined rapidly when he and other UNIA members were indicted for mail fraud in 1922 in connection with the sale of stock for the Black Star Line. He served two years of a five-year prison term, but in 1927 his sentence was commuted by U.S. Pres. Calvin Coolidge, and he was deported as an undesirable alien. He was never able to revive the movement abroad, and he died in virtual obscurity.

In 1920, more than 20,000 people attended Garvey’s first UNIA convention in New York. The convention produced a Declaration of Negro Rights, which denounced lynchings, segregated public transportation, job discrimination, and inferior black public schools. The document also demanded “Africa for the Africans.” Without actually consulting any African people, the convention proclaimed Garvey the “Provisional President of Africa.”

Garvey believed that white society would never accept black Americans as equals. Therefore, he called for the separate self-development of African Americans within the United States.

The UNIA set up many small black-owned businesses such as restaurants, groceries, a publishing house, and even a toy company that made black dolls. Garvey’s goal was to create a separate economy and society run for and by African Americans.

Ultimately, Garvey argued, all black people in the world should return to their homeland in Africa, which should be free of white colonial rule. Garvey had grand plans for settling black Americans in Liberia, the only country in Africa governed by Africans. But, Garvey’s UNIA lacked the necessary funds and few blacks in the United States indicated any interest in going “back to Africa.”

A poor economy and the near-bankruptcy of the Black Star Line caused Garvey to seek more dues-paying members for the UNIA. He launched a recruitment campaign in the South, which he had ignored because of strong white resistance.

In a bizarre twist, Garvey met with a leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Atlanta in 1922. Garvey declared that the goal of the UNIA and KKK was the same: completely separate black and white societies. Garvey even praised racial segregation laws, explaining that they were good for building black businesses. Little came of this recruitment effort. Criticism from his followers grew.

In 1922, the U.S. government arrested Garvey for mail fraud for his attempts to sell more stock in the failing Black Star Line. At his trial, the evidence showed that Garvey was a businessman, but the facts were less clear about outright fraud. The jury convicted him anyway, and he was sentenced to prison.

In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge commuted his sentence, and he was released. The government immediately deported him to Jamaica.