Lutuli was heir to a tradition of tribal leadership. His grandfather was chief of his small tribe at Groutville in the Umvoti Mission Reserve near Stanger, Natal, and was succeeded by a son. Lutuli’s father was a younger son, John Bunyan Lutuli, who became a Christian missionary and spent most of the last years of his life in the missions among the Matabele of Rhodesia. Lutuli’s mother, Mtonya Gumede, spent part of her childhood in the household of King Cetewayo but was raised in Groutville. She joined her husband in Rhodesia where her third son, Albert John, was born in what Lutuli calculates would probably have been 1898.

Supported by a mother who was determined that he get an education, Albert John Lutuli went to the local Congregationalist mission school for his primary work. He then studied at a boarding school called Ohlange Institute for two terms before transferring to a Methodist institution at Edendale, where he completed a teachers’ course about 1917. After leaving a job as principal of an intermediate school, which he held for two years (he was also the entire staff, he says in his autobiography) – he completed the Higher Teachers’ Training Course at Adams College, attending on a scholarship. To provide financial support for his mother, he declined a scholarship to University College at Fort Hare and accepted an appointment at Adams, as one of two Africans to join the staff.

A professional educator for the next fifteen years, Lutuli then and afterward contended that education should be made available to all Africans, that it should be liberal and not narrowly vocational in nature, and that its quality should be equal to that made available to white children. In 1928 he became secretary of the African Teacher’s Association and in 1933 its president.

Lutuli was also active in Christian church work, being a lay preacher for many years. As an adviser to the organized church, he became chairman of the South African Board of the Congregationalist Church of America, president of the Natal Mission Conference, and an executive member of the Christian Council of South Africa. He was a delegate to the International Missionary Conference in Madras in 1938 and in 1948 spent nine months on a lecture tour of the United States, sponsored by two missionary organizations.

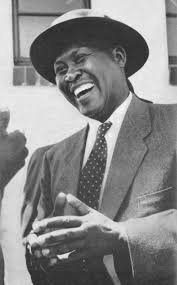

In 1927 Lutuli married a fellow teacher, Nokukhanya Bhengu. They established their permanent home in Groutville, where in 1929 the first of their seven children was born. In 1933 the tribal elders asked Lutuli to become chief of the tribe. For two years he hesitated, for he was loath to give up his profession and the financial security it afforded. He accepted the call in early 1936 and, until removed from this office by the government in 1952, devoted himself for the next seventeen years to the 5,000 people who made up his tribe. He performed the judicial function of a magistrate, the mediating function of an official acting as a representative of his people and at the same time as a representative of the central government, the tribal function of a presiding dignitary at traditional festivities, and the executive function of a leader seeking a better life for his people.

As the restrictions imposed by the Union government on nonwhites became increasingly complete, Lutuli’s concern for his race transcended the tribal level to encompass the welfare of all black South Africans, and indeed of all South Africans. In 1936 the government disenfranchised the only Africans who had voting rights – those in Cape Province; in 1948 the Nationalist Party, in control of the government, adopted the policy of apartheid, or “total apartness”; in the 1950s the laws known as the Pass Laws, circumscribing the freedom of movement of Africans, were tightened; and throughout this period laws were added which put limitations on the African in almost every aspect of his life.

In 1944 Lutuli joined the African National Congress (ANC), an organization somewhat analogous to the American NAACP whose objective was to secure universal enfranchisement and the legal observance of human rights. In 1945 he was elected to the Committee of the Natal Provincial Division of ANC and in 1951 to the presidency of the Division. The next year he joined with other ANC leaders in organizing nonviolent campaigns to defy discriminatory laws. The government, charging Lutuli with a conflict of interest, demanded that he withdraw his membership in ANC or forfeit his office as tribal chief. Refusing to do either voluntarily, he was dismissed from his chieftainship, for chiefs hold office at the pleasure of the government even though elected by tribal elders.

A month later Lutuli was elected president-general of the ANC. Responding immediately, the government sought to minimize his effectiveness as a leader by banning him from the larger South African centers and from all public meetings for two years. Upon the expiration of that ban, he went to Johannesburg to address a meeting but at the airport was served with a second ban confining him to a twenty-mile radius of his home for another two years. When this second ban expired, he attended an ANC conference in 1956, only to be arrested and charged with treason a few months later, along with 155 others. After being held in custody for about a year during the preliminary hearings, he was released in December, 1957, and the charges against him and sixty-four others were dropped.

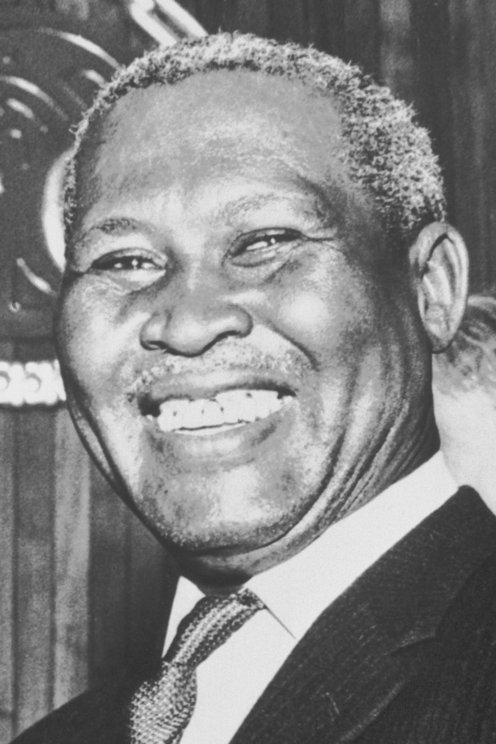

Lutuli’s return to active leadership in 1958 was cut short by the imposition of a third ban, this time a five-year ban prohibiting him from publishing anything and confining him to a fifteen-mile radius of his home. The ban was temporarily lifted while he testified at the continuing treason trials (which ended with a verdict in 1961 absolving ANC of Communist subservience and of plotting the violent overthrow of the government). It was lifted again in March 1960, to permit his arrest for publicly burning his pass – a gesture of solidarity with those demonstrators against the Pass Laws who had died in the “Sharpeville massacre”.

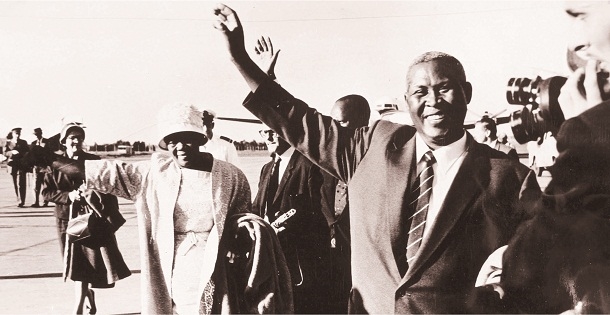

The Pan-Africanist Congress, not the African National Congress, had called the demonstration, but in the ensuing state of emergency that was officially declared, Parliament outlawed both organizations and apprehended their leaders. Lutuli was found guilty, fined, given a jail sentence that was suspended because of the precarious state of his health and returned to the isolation of Groutville. One final time the ban was lifted, this time for ten days in early December of 1961 to permit Lutuli and his wife to attend the Nobel Peace Prize ceremonies in Oslo.

A fourth ban to run for five years confining Lutuli to the immediate vicinity of his home was issued in May 1964, the day before the expiration of the third ban. Still, Lutuli remained undiminished in the public mind.

The South African Colored People’s Congress nominated him for president, the National Union of South African Students made him its honorary president, the students of Glasgow University voted him their rector and the New York City Protestant Council conferred an award on him. Despite the publication ban, his autobiography circulated in the outside world, and his name appeared on human rights petitions presented to the UN.

For fifteen years or so before his death, Lutuli suffered from high blood pressure and once had a slight stroke. With age, his hearing and eyesight also became impaired – perhaps a factor in his death. In July 1967, at the age of sixty-nine, he was fatally injured when he was struck by a freight train as he walked on the trestle bridge over the Umvoti River near his home.