The trans-Atlantic slave trade was the capture, forcible transport, and sale of native Africans to Europeans for lifelong bondage in the Americas. Lasting from the 16th to 19th centuries, it is responsible, more than any other project or phenomenon in the history of the modern world, for the creation of the African diaspora—the dispersal of Black people outside their places of origin on the continent of Africa.

As a result of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, there are presently 51.5 million people of African descent living in North America (United States, Mexico, and Canada), approximately 66 million in South America, 1.9 million in Central America, and more than 14.5 million throughout the islands of the Caribbean. Over centuries of transformation and upheaval, these diasporic peoples have developed rich cultural traditions, distinct societies, and independent nations—all sharing elements of a common African heritage.

Triangular Trade

The trans-Atlantic slave trade was one leg of a three-part system known as the triangular trade. The forming of the triangle began when European ships, carrying firearms and manufactured goods, sailed to Africa, where the commodities were traded for enslaved men, women, and children. Next, the same ships transported human cargo across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas.

This horrific journey was called the Middle Passage. Completing the triangle, the ships—having disembarked the enslaved Africans—were reloaded with cotton, sugar, tobacco, and other cash crops produced by slave labor, and returned to Europe.

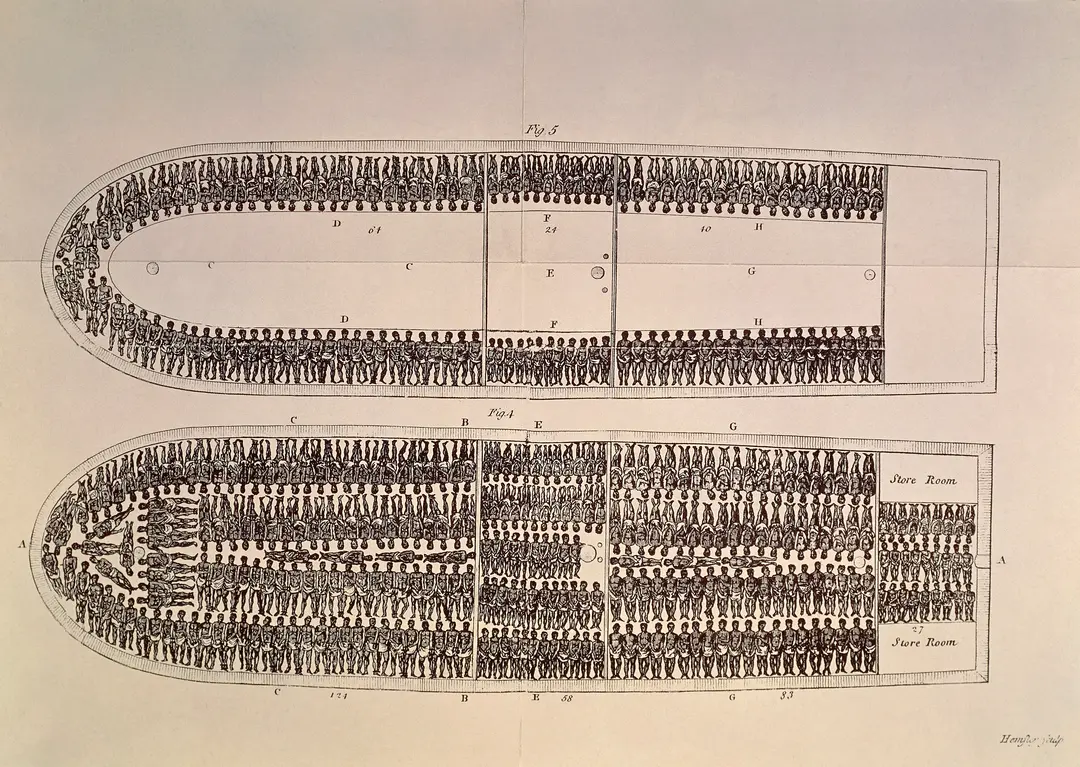

A diagram of the interior of a slave ship from the Atlantic slave trade shows how captured humans were crammed into ships for their journey to the Americas where they were sold.

A diagram of the interior of a slave ship from the Atlantic slave trade shows how captured humans were crammed into ships for their journey to the Americas where they were sold.

The triangular trade generated incredible wealth for the European and American nations that participated in it—at the expense of millions of human lives. An estimated 1.8 million Africans perished during the Middle Passage.

The countries that enslaved the highest number of Africans, from the most to the least, were Portugal, Britain, France, the Netherlands, Spain, the United States, and Denmark—shipping a total of 12.5 million enslaved Africans to toil in what was considered the “New World.”

Other European nations, such as Germany and Sweden, took part in the trade indirectly or for a brief period. Canada, generally omitted from slavery history, was involved in slaveholding, first as a French colony, and then as part of the British Empire.

“Little is known about Canadian slavery, both inside and outside of the nation,” says Charmaine A. Nelson, director of the newly founded Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery at NSCAD University, in Halifax. “It is a national amnesia.”

Fellow Africans' Role in the Slave Trade

Another downplayed factor is the central role played by ruling African states in the capture and sale of fellow Africans to European traders—an estimated 90 percent of all captives. The main motivation behind these transactions was the acquisition of guns for use in inter-ethnic warfare. The enslaved were abducted from as far north as present-day Senegal to as far south as Angola, and transported to destinations as far south as Argentina and as far north as New England.

Dehumanizing in all locations, the practice of slavery still could vary from place to place. This variation accounts for demographic, cultural and even genetic distinctions among modern diasporic Black populations.

A July 2020 genetic study found that enslaved women contributed more than enslaved men to the modern-day gene pool of people of African descent in the Americas. The findings also show that Caucasian men contributed more than Caucasian women, confirming the well-documented practice of sexual violation of enslaved women.

African Communities Beyond the Americas

Predating the trans-Atlantic slave trade was eastward and northbound slave-trading enterprises known broadly as the Arab Slave Trade. They contributed significantly to the creation of an African diasporic presence in the Old World.

“People from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, and the Swahili Coast were deported as slaves to the Indian Peninsula,” says Sylviane A. Diouf, a historian of the African diaspora who co-curated the 2013 exhibition, “Africans in India: From Slaves to Generals and Rulers” at New York’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

“From the 1300s, many of these Africans and their descendants became generals, admirals, architects, high-ranking officials, prime ministers, and rulers, immortalized in numerous portraits. They also founded the states of Janjira and Sachin, where they ruled over Hindu and Jewish majorities.”

The Arab and trans-Atlantic slave trades inevitably coincided, if not in their commercial dealings, in their human exploitation. It is known that continental Africans were taken to the island of Madagascar by Arab enslavers from as early as the 10th century. In the 18th century, European enslavers took up operations on the island, transporting roughly 6,000 people in shackles to U.S. slave markets. Though these Madagascans constituted a tiny percentage of the total enslaved population, their DNA is identifiable to this day among their living descendants, such as the actor Maya Rudolph and director Keenan Ivory Wayans.

To satisfy different European fascinations, enslaved Africans were also taken to Europe.

“Among British royals, nobles, ship captains and merchants, a trend began of keeping Africans as entertainment, curiosities, and sometimes surrogate sons,” says Monica L. Miller, author of Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity. “In almost all cases, these Black men were extravagantly clothed in the latest fashions or liveries—forced foppishness.”

Role of Resistance

For the nearly four centuries before its abolition by all nations involved, “the trans-Atlantic slave trade not only influenced the composition of slave communities in the Americas, it also powerfully shaped slave resistance,” according to Marjoleine Kars, author of Blood on the River: A Chronicle of Mutiny and Freedom on the Wild Coast.

“Take, for instance, the Berbice slave rebellion of 1763-1764. Lasting more than a year, the rebellion took place in a small Dutch colony on the Caribbean coast of South America in February of 1763. Enslaved people, led by a man named Coffij, or Kofi, rose up, set the Dutch fleeing, and took control of the colony.”