Eritrea is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It has a long and complex history, dating back to ancient times. It was part of the Kingdom of Aksum in the first century AD and later became part of the Ottoman Empire. In the late 19th century, it was colonized by Italy, and after World War II, it became a United Nations Trust Territory. In 1993, Eritrea declared its independence from Ethiopia, and it has since become a sovereign nation. Today, Eritrea is a multi-ethnic country with a population of around 6 million people.

Between 1869 and 1885, Eritrea was part of the Ottoman Empire. During this period, the Ottoman Empire was in decline, and the region was largely neglected. In 1885, Italy declared a protectorate over the region and began to colonize it. This period of Italian colonization lasted until 1941 when the British took control of the region.

During the first half of the century, with the Italians in possession of Eritrea, Ethiopia has been landlocked. The defeat of Italy in World War II gives Haile Selassie the chance to redress this deficiency. In a meeting with President Roosevelt in 1945 he stresses his need for access to the sea through the possession of Eritrea, an area loosely linked with Ethiopia at various periods in the past.

The USA, seeing the chance of a naval base in the Red Sea at Massawa, shares an interest in this development. When the United Nations considers the future of Eritrea, in 1948-50, Washington applies pressure for its annexation by Ethiopia.

The UN decision, given in 1950, is that Eritrea shall become part of Ethiopia from 1952, as an autonomous federal province with its own constitution and elected government. In that year an Eritrean administration duly takes control, bringing to an end the temporary British rule in the region.

Within Eritrea opinion has been divided, largely along Christian versus Muslim lines, on the question of union with Christian Ethiopia. On one side is the Unionist Party, founded in 1946 with financial assistance from Addis Ababa. On the other is the Muslim League, set up a year later to campaign for Eritrean independence. In the election, the Unionists fail to win an outright majority. The Eritrean government is therefore at first a coalition.

Aware that there will be continuing agitation for independence, Haile Selassie shamelessly interferes to secure his aim of union. With his help, the Unionists remove Muslims from government jobs, put an end to teaching in Arabic, ban all other political parties (1958) and trade unions (1959), introduce Ethiopian law, and even give the Eritrean government a new name. It becomes merely the Eritrean administration.

In these circumstances, and with the persecuted leaders of the independence movement now abroad, the result is a foregone conclusion when the Ethiopian and Eritrean parliaments debate the question of union in November 1962.

On a unanimous vote in both Addis Ababa and Asmara, it is agreed that Eritrea's federal status within Ethiopia shall be abolished. The area is now to become a province like any other in the Ethiopian empire.

By the same token, this degree of unanimity also exists now on the opposing side. In 1960 Eritrea's Muslim leaders, living in exile, form the ELF or Eritrean Liberation Front to fight for independence. By the mid-1960s they have a guerrilla force operating in western Eritrea. And in a few years, they cease to be a purely Muslim movement. Soon after the union of 1962 Haile Selassie interferes in Tigre's schools, banning Tigrinya, the local language, and replacing it with Amharic. This converts many Tigre Christians to the cause of independence.

The period from 1970 to 1974, when the ELF and the newly-emerged EPLF fought a civil war, is a bleak period in Eritrea's history. This ended when the revolution in Ethiopia made it imperative for the fronts to hold a common position to confront any proposals that might come from Addis. By this time the EPLF was establishing itself as a powerful force. During 1974/75 it further strengthened itself by successfully recruiting Eritreans with military training from the Ethiopian police force in Eritrea, and from Eritrean commando units which it had successfully defeated. A large influx of young people joined the EPLF after 56 students were garroted with an electric cable in Asmara in January 1975.

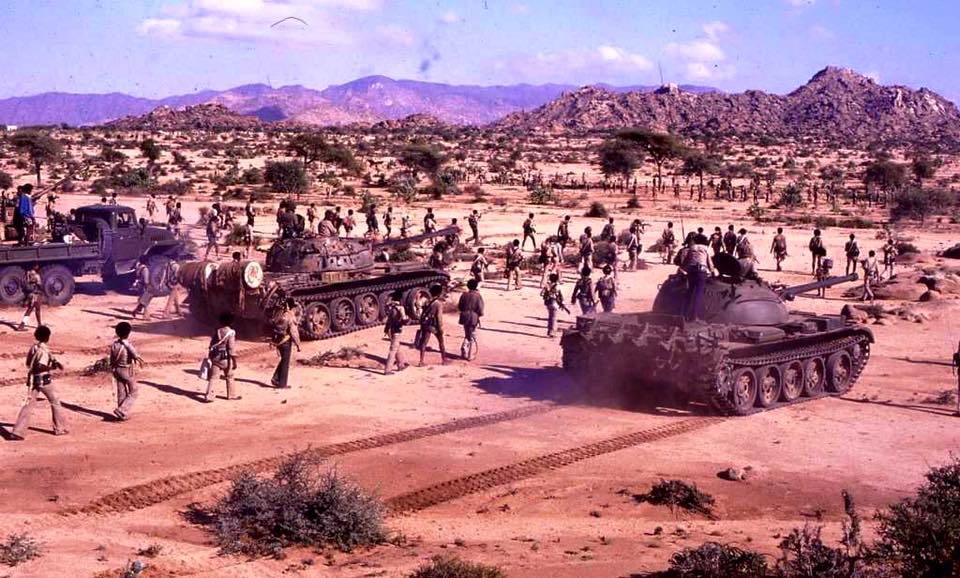

By mid-1976, began the launching of the 'Peasant Army' offensive against Eritrea. The Eritrean guerrilla forces (estimated to number 20,000) managed to win considerable victories against the occupying Ethiopians. The EPLF laid siege to Nacfa in September 1976. In 1977 they took Karora, Afabet, Elaberet, Keren and Decemhare. They also surrounded Asmara, Eritrea's capital, and organized the escape of 1,000 political prisoners from Asmara's jail.

The ELF took Tessenei, Agordat and Mendefera. By the end of 1977, mainland Massawa was in the hands of the EPLF, which now had captured tanks and armored vehicles. They were close to final victory in early 1978 but had not planned on the Soviet Union's crucial intervention in the form of military aid for Mengistu's regime in Ethiopia.

Italian influence (1885 - 1941)

The first Italian mission in Abyssinia was at Adua in 1840, under Father Giuseppe Sapeto. He was the vehicle through which the Italian government brought up pieces of land near Assab, initially on behalf of the national Rubattino Shipping Company. But as the European 'Scramble for Africa' gathered pace, the Italian government took over the land in 1882 and began to administer it directly. They also ousted the Egyptians from Massawa on the coast. However, expansion further inland soon led to clashes with Emperor Yohannes. In 1887, Ras Alula's forces inflicted a heavy defeat on the Italians at Dogali, forcing them to retreat.

This was a significant victory for Yohannes, who was also facing a number of other threats on different fronts at the same time - not only the Italians but the Dervishes and Menelik, an increasingly disloyal general. Yohannes was eventually killed after being captured in battle against the Dervishes at Galabat. Following his death, Ras Alula withdrew to Tigray. This allowed Menelik to be named Yohannes successor in 1889 with substantial Italian backing, instead of the natural heir, Ras Mangasha.

The Italians then moved rapidly, taking Keren in July 1889 and Asmara one month later. Melenik had signed the Treaty of Uccialli with the Italians the same year, detailing the areas each controlled. Just four years later, Melenik renounced the treaty over a dispute arising from further Italian expansionist attempts. After more military clashes and in the face of sizable Italian reinforcements, Melenik signed a peace treaty. Italy then began establishing colonial rule in the areas it controlled, as defined in the treaties with the Ethiopian emperor in 1900, 1902, and 1908.

The Italians colonized Eritrea by establishing military outposts and settlements throughout the region. They also imposed taxes and other restrictions on the local population and used forced labor to build infrastructure and develop the economy. In addition, they introduced new laws and regulations and imposed their own language and culture on the local population.

Colonial rule

The Italians initially used a system of indirect rule through local chiefs at the beginning of the 20th century. The first decade or so concentrated on the expropriation of land from indigenous owners. The colonial power also embarked on the construction of the railway from Massawa to Asmara in 1909. The fascist rule in the 1920s and the spirit of 'Pax Italiana' gave a significant boost to the number of Italians in Eritrea, adding further to the loss of land by the local population.

In 1935, Italy succeeded in overrunning Abyssinia and decreed that Eritrea, Italian Somali land, and Abyssinia were to be known as Italian East Africa. The development of regional transport links at this time around Asmara, Assab, and Addis produced a rapid but short-lived economic boom.

However, there began to be clashes between Italian and British forces in 1940. Under General Platt, the British captured Agordat in 1941, Taking Keren and Asmara later that year. As Britain did not have the capacity to take over the full running of the territory, they left some Italian officials in place. One of the most significant changes under the British was the lifting of the color bar which the Italians had operated. Eritreans could now legally be employed as civil servants. In 1944, with the changing fortunes of world war II, Britain withdrew resources from Eritrea. The postwar years and economic recession led to comparatively high levels of urban unemployment and unrest.

Soviet intervention (1977 - 1988)

The Soviet Union intervened in December 1977. The Soviet navy, by shelling EPLF positions from their battleships, prevented the EPLF from taking the port section of Massawa. A massive airlift of Soviet tanks and other arms allowed the Ethiopian army to push back the Somali forces in the Ogaden, and by May/June 1978 these troops and heavy Armour were available for redeployment in Eritrea. In two offensives the Ethiopian army retook most of the towns held by the Eritrean fronts.

For the EPLF the return to the northern base areas was 'a strategic withdrawal'. It minimized civilian and military casualties. It also allowed the EPLF to give battle at strategic points of its choosing, evacuate towns, and remove plants and equipment from its base area.

For the ELF the story was different. In attempting to hold territory its casualties were high. The balance of military power between the fronts had now shifted strongly towards the EPLF. Recognizing its weaker position, worsened by ethnic disputes, the ELF began in 1979 to respond to the Soviet proposals. In return for its agreement to autonomy within Ethiopia, the ELF was offered the reins of government in Eritrea, while the EPLF stood for a secular and socialist state of Eritrea, rejecting ethnic differences.

A bitter civil war between the ELF and the EPLF resulted, and the EPLF finally won in 1981. ELF fighters either changed sides or fled to Sudan, and the EPLF became the single front with a military presence in Eritrea. The EPLF successfully resisted offensives in 1982 and 1983, while the Dergue organized genocidal responses to eliminate the broad civil support for the EPLF liberation movement. But the EPLF lines held and the morale and confidence of the EPLF were given massive boost while the Ethiopian army was demoralized. Its net effect was to strengthen the range of military equipment at the EPLF's disposal.

Through most of the war, Ethiopia occupied the southern part of Eritrea. The EPLF had to settle in the inhospitable northern hills towards the Sudanese border. These hills became a safe haven for the families of soldiers and the orphans and disabled. Consequently, much of the regions around Afabet and Nacfa in Sahel province became home to makeshift homes, schools, orphanages, hospitals, factories, printers, bakeries, etc. in an attempt to live life as normally as possible under extraordinary conditions. Most structures were built either into the ground or in caves to avoid being bombed by Ethiopian jets. The steep narrow areas were chosen as they were the hardest for the jets to negotiate.

In 1984, while Mengistu was spending lavishly on a celebration of the tenth anniversary of his glorious revolution, one-sixth of the population of Ethiopia was in danger of dying of starvation, and ten thousand people per week were already dying. As part of the "politics of famine", Mengistu began using his power to block delivery of grain to areas he considered hostile to him, most notably Tigray and Eritrea. Innocent people starved to death while grain sat undelivered.

The victory (1988 - 1993)

At the end of the 1980s, the Soviet Union informed Mengistu that it would not be renewing its defense and cooperation agreement with Ethiopia. With the withdrawal of Soviet support and supplies, the Ethiopian Army's morale plummeted and the EPLF began to advance on Ethiopian positions. In 1988, the EPLF captured Afabet, the headquarters of the Ethiopian Army in northeastern Eritrea, prompting the Ethiopian Army to withdraw from its garrisons in Eritrea's western lowlands. EPLF fighters then moved into position around Keren, Eritrea's second-largest city.

The EPLA (military branch of the EPLF) by this time includes twelve infantry brigades (some 20,000 fighters), 200 tanks and armored vehicles, and a fleet of fast attack speedboats, all captured in battle and in guerrilla raids from the Ethiopians. EPLA's disadvantageous combat ratio ranged from 1:4 to 1:8, but the battlefield mortality ratio was at least ten Ethiopians to one Eritrean, due to better-trained and more committed fighters.

In 1990 the EPLF had captured the strategically important port of Massawa, and they entered Asmara, now the capital of Eritrea, in 1991. The Ethiopian army under Haile Mariam Mengistu (an army officer who deposed Haile Selassie in 1974) intensified the war against Eritrea, but it was easily defeated in 1991 after Mengistu fell from power.

It was at 10:00 a.m. on May 24, 1991 that Asmara residents realized EPLF fighters had entered their city. In a spontaneous outburst of happiness and relief, Asmarinos flung open their doors and rushed into the streets to dance in jubilation, some still in their pajamas. The dancing lasted for weeks.

At a conference held in London in 1991 the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), who were now in control of Ethiopia having ousted Mengistu and were sympathetic to Eritrean nationalist aspirations, accepted the EPLF as the provisional government of Eritrea. So began the long process towards independence and international legitimation of Eritrea as a country in its own right.

In April 1993 a referendum was held in which 1,102,410 Eritreans voted; 99.8% endorsed national independence and on May 28 Eritrea became the 182nd member of the UN. Later that year, Eritreans elected their first president, Isaias Afewerki, formerly secretary-general of the EPLF.

Thus it is now eligible to receive international aid to help reconstruct and develop its shattered economy. Since establishing a provisional government in 1991, Eritrea has been a stable and peaceful political entity, with all political groups represented in the transitional government.

The war has had a devastating effect on Eritrea. Around 60,000 people lost their lives, there are an estimated 50,000 children with no parents, and 60,000 people who have been left handicapped. However, there is now great optimism with people pulling together to rebuild the country. The National Service, announced on July 14th 1994, required all women and men over eighteen to undergo six months of military training and a year of work on national reconstruction. This helped to compensate for the country's lack of capital and to reduce dependence on foreign aid, while welding together the diverse society.