Histories of Liberia generally begin with the arrival of the Portuguese traders in the mid-1400s, and the rise of the trans-Atlantic trade. Coastal groups traded several goods with Europeans, but the area became known as the Grain Coast, because of its rich supply of malagueta pepper grains.

In 1816, the future of Liberia changed dramatically due to the formation of the American Colonization Society (ACS) in the United States. Looking for a place to re-settle free-born Black Americans and formerly enslaved people, the ACS chose the Grain Coast.

In 1822, the ACS founded Liberia as a colony of the United States of America. Over the next few decades, 19,900 Black American men and women migrated to the colony.

On July 26, 1847, Liberia declared its independence from America. Interestingly, the United States refused to acknowledge Liberia’s independence until 1862, when the U.S. government ended the practice of enslavement during the American Civil War.

The oft-stated claim that after the Scramble for Africa, Liberia was one of two African states to remain independent is misleading because the indigenous African societies had little economic or political power in the new republic.

Instead, all power was concentrated in the hand of the African American settlers and their descendants, who became known as Americo-Liberians. In 1931, an international commission revealed that several prominent Americo-Liberians had enslaved indigenous people.

The Americo-Liberians Rule

The Americo-Liberians constituted less than 2 percent of Liberia's population, but in the 19th and early 20th centuries, they made up nearly 100 percent of qualified voters. For over 100 years, from its formation in the 1860s until 1980, the Americo-Liberian True Whig Party dominated Liberian politics, in what was essentially a minority-ruled one-party state. Though they were Black, the Americo-Liberians created a cultural divide. From the day they arrived, they set about establishing an American rather than African culture. They spoke English, dressed like Americans, built Southern plantation-style homes, ate American foods, practiced Christianity, and lived in monogamous relationships. They modeled the Liberian government after that of the United States.

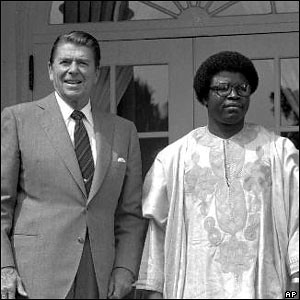

On April 12, 1980, Master Sgt. Samuel K. Doe and less than 20 soldiers overthrew the Americo-Liberian president, William Tolbert. The Liberian people celebrated the coup d'etat as liberation from Americo-Liberian domination. However, Doe’s dictatorial government proved no better for the Liberian people than its predecessor. After a coup attempt against him in 1985 failed, Doe responded with brutal atrocities against suspected conspirators and their followers.

The United States, however, had long used Liberia as an important base of operations in Africa, and during the Cold War, the U.S. provided millions of dollars in aid that helped prop up Doe’s increasingly unpopular regime.

1980: End of Americo-Liberian rule

Liberia began to change during the 1970s. In 1971, William Tubman, Liberia’s president of 27 years, died while in office. Tubman’s “Open Door” economic policy brought a great deal of foreign investment at a heavy price, as the divide widened between the prospering Americo-Liberians (benefiting from such investment) and the rest of the population. Following Tubman’s death, his long-serving vice president, William Tolbert, assumed the presidency. Because Tolbert was a member of one the most influential and affluent Americo-Liberian families, everything from cabinet appointments to economic policy was tainted with allegations of nepotism. However, Tolbert was also the first president to speak an indigenous language, and he promoted a program to bring more indigenous persons into the government. Unfortunately, this initiative lacked support within Tolbert’s own administration, and while the majority felt the change was occurring too slowly, many Americo-Liberians felt it was too rapid. In April 1979, a proposal to raise the price of rice (which the Tolbert administration subsidized) met with violent opposition. The government claimed that the price increase was meant to promote more local farming, slow the rate of urban migration, and reduce dependence on imported rice.

However, opposition leaders also pointed out that the Tolbert family controlled the rice monopoly in Liberia and therefore stood to prosper. The ensuing “rice riots” severely damaged Tolbert’s credibility and increased the administration’s vulnerability. In April 1980, Army Master Sergeant Samuel Doe, an ethnic Krahn, led a coup d’etat that resulted in Tolbert’s murder and the public execution of 13 of his cabinet members. Among the many Liberians that fled the country was then–Minister of Finance, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf.

Civil Wars

In 1989, Charles Taylor, a former Americo-Liberian official, invaded Liberia with his National Patriotic Front. Backed by Libya, Burkina Faso, and the Ivory Coast, Taylor soon controlled much of the eastern part of Liberia. Doe was assassinated in 1990, and for the next five years, Liberia was divided up between competing warlords, who made millions exporting the country's resources to foreign buyers.

In 1996, Liberia's warlords signed a peace agreement and began converting their militias into political parties. The peace, however, did not last. In 1999, another rebel group, Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) challenged Taylor's rule. LURD reportedly gained support from Guinea, while Taylor continued to support rebel groups in Sierra Leone.

By 2001, Liberia was fully embroiled in a three-way civil war, between Taylor's forces, LURD, and a third rebel group, the Movement for Democracy in Liberia.

In 2002, a group of women, led by social worker Leymah Gbowee, formed the Women of Liberia, Mass Action for Peace, a cross-religious organization, that brought Muslim and Christian women together to work for peace. Today, the women’s galvanizingly effective efforts are credited with bringing about a peace agreement in 2003.

Recent History

As part of the agreement, Charles Taylor agreed to step down. In 2012, he was convicted of war crimes by the International Court of Justice and sentenced to 50 years in jail.

In 2005, elections were held in Liberia, and Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, who had once been arrested by Samuel Doe and lost to Taylor in the 1997 elections, was elected President of Liberia. She was Africa's first female head of state.

While there have been some critiques of her rule, Liberia has remained stable and made significant economic progress. In 2011, President Sirleaf was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, along with Leymah Gbowee of the Mass Action for Peace and Tawakkol Karman of Yemen, who also championed women’s rights and peacebuilding.

Culture

Liberia’s culture draws from the Southern U.S. heritage of its Americo-Liberian settlers and the people of the country’s 16 indigenous and migratory groups. English remains the official language of Liberia, though the languages of the indigenous peoples are widely spoken. About 85.5% of Liberia's population practices Christianity, while Muslims comprise 12.2% of the population.

The embroidery and quilting skills of its Black American settlers are now firmly embedded in Liberian art, while the music of the American South blends with ancient African rhythms, harmonies, and dance. Christian music is popular, with hymns sung a-cappella in the traditional African style.

In literature, Liberian authors have contributed to the writings of genres ranging from folk art to human rights, equality, and diversity. Among the most influential Liberian authors, W. E. B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey wrote of the need for Africans to develop their own “Africa for Africans!” identity, demand self-rule, and reject the European view of Africa as having a cultureless society.

Education is compulsory for Liberian children between ages 7 and 16 and is provided free at the primary and secondary levels. The country’s main institutes of higher learning include the University of Liberia, Cuttington University College, and the William V.S. Tubman College of Technology.

Ethnic Groups

The Liberian population is made up of several indigenous ethnic groups who migrated from Sudan during the late Middle Ages. Other groups include the ancestors of the Black Americo-Liberians who migrated from America and founded Liberia between 1820 and 1865 and other Black immigrants from neighboring countries of West Africa.

The 16 officially recognized ethnic groups, who make up about 95% of the population, include the Kpelle; Bassa; Mano; Gio or Dan; Kru; Grebo; Krahn; Vai; Gola; Mandingo or Mandinka; Mende; Kissi; Gbandi; Loma; Dei or Dewoin; Belleh; and Americo-Liberians.

Government

Still modeled on the United States federal government, Liberia’s government is a republic with a representative democracy made up of executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

Under its constitution adopted in January 1986, a president, who is freely elected to a six-year term, serves as the head of state and commander in chief of the military. Members of the legislative two-chamber National Assembly are elected to six-year terms in the House of Representatives and nine-year terms in the Senate. Similar to the hierarchical power structure of federalism in the United States, Liberia is divided into 15 counties, each headed by a presidentially appointed superintendent.

After being legalized in 1984, political parties multiplied rapidly. Current major parties include the Unity Party, the Congress for Democratic Change, the Alliance for Peace and Democracy, and the United People’s Party.

As highlighted by the election of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf as president in 2005, women play a prominent role in Liberian politics and government. Since 2000, women have held over 14% of the seats in the National Assembly. Several women have also served in the presidential cabinet and as Supreme Court justices.

The Liberian judicial system is overseen by a Supreme Court, with a lower court system comprised of courts of appeals, criminal courts, and local magistrate courts. To the extent possible the indigenous ethnic groups are allowed to govern themselves according to their traditional laws.