The people of Kru are a tribe of West Africa from South-Eastern Liberia and the neighboring Côte d’Ivoire. The Kru people have historical relations with Nigeria’s Ijaws.

Kru migrated and settled in different parts of the West African coasts, in particular Sierra Leone, Freetown, Cameroon, and Nigeria.

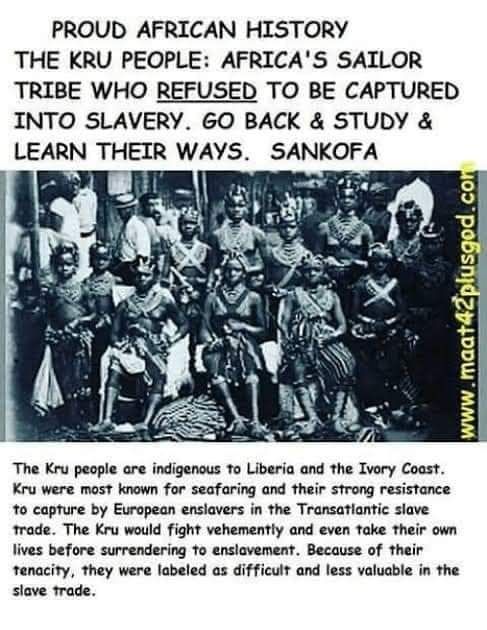

The Kru tribe who made fishing and trading their primary activity was majorly known for their seafaring and strong history of resistance to being captured for the slave trade by European slave traders, that was when Liberia was called the Republic of Maryland.

Often, Kru people would first take their own lives, or fight fiercely to avoid getting caught and taken away. They also rejected the efforts of settlers to control their trade and were labeled as difficult and less valuable in the slave trade because of their toughness.

The Key people had tattooed their foreheads and nose bridge with indigo dye to distinguish them from the slaves. The Kru tribe was made up of 24 sub-clans with differences in language dialect and some cultural norms.

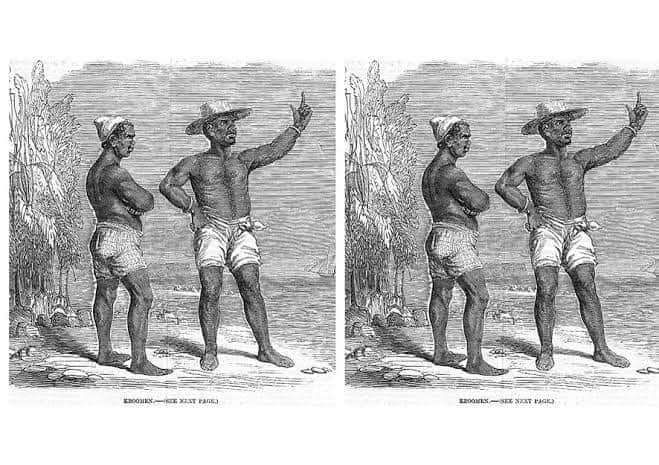

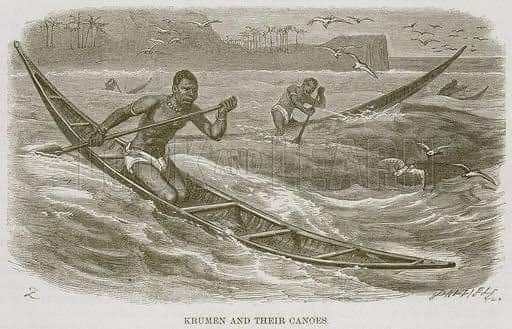

And apart from their dominance of resistance, the Kru were distinguished by the ability to effectively monitor the seas.

Their canoeing and surfing skills earned them a good knowledge of the fast ocean currents that later gave them work on British merchants and warships.

It has been documented in European history that the people established mutual relationships with European traders and explorers prior to the arrival of the freed slaves from North America to West Africa.

It is from this relationship that the Klao ethnic group was known as Kroo or Kru by the Europeans in this region. Kru’s name emerged from the word ‘gang.’ They were given the name as a result of their career.

Today the Kru is one of Liberia’s many ethnic groups, numbering about 7% of the population. Their language is one of the key languages spoken, too. By the end of the 20th century, Kru probably was more outside than inside of the tribal territory. At the end of the 20th century, Monrovia was the biggest single community of Kru.

History

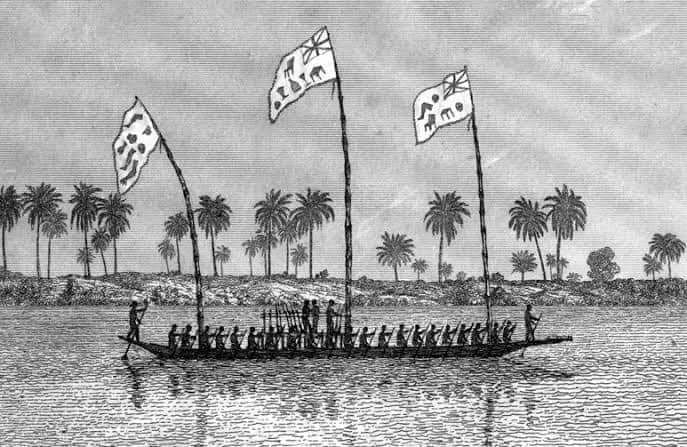

During the Atlantic slave trade, Kru people were considered more valuable as traders and sailors on slave ships than as slave labor, and Kru oral traditions strongly hold that they were never enslaved. To ensure their status as “freemen,” they initiated the practice of tattooing their foreheads and the bridge of their nose with indigo dye to distinguish them from slave labor. Many were called Krumen by Europeans, and hired as free sailors on European ships in both the slave trade and trade in goods. The Kru sailors were famous for their skills in navigating and sailing the Atlantic. Their maritime expertise evolved along the west coast of Africa where they made a living as fishermen and traders. Knowing the in-shore waters of the western coast of Africa, and having nautical experience, they were employed as sailors, navigators and interpreters aboard slave ships, trading ships, and American and British warships used against the slave trade.

The Kru history is one marked by a strong sense of ethnicity and resistance to occupation. In 1856 when part of Liberia was still known as the independent Republic of Maryland, the Kru along with the Grebo resisted Maryland settlers' efforts to control their trade. They were also infamous amongst early European slave raiders as being especially resistant to the slave trade.

Origin

The coast of eastern Liberia and western Ivory Coast were rarely visited by European vessels until the nineteenth century, and for that reason, few written texts can illuminate its early history or the origin of the Kru communities there. Oral tradition remains the most important key to the origin of the Kru.

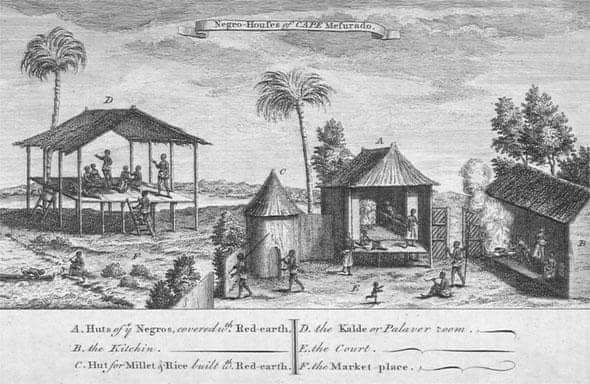

Traditions recorded in the mid-nineteenth century by James Connelly relate that the Kru communities that lived along the shore of what is today southern Liberia and the reputed core settlement of the Kru came down to the coast from the interior "some three generations back — say one hundred to one hundred fifty years..." from an original place he called Claho. Coming down the Poor River they "learned the value of salt" and founded the town of Bassa. They subsequently moved again to Little Kroo and then were subsequently joined by more Kru-speaking communities from the interior. These events likely occurred in the 18th century and are believed to be connected to more intensive European interest in trade in the region at this time. The original settlers from the interior eventually established five towns: Little Kroo, Setra Kroo, Kroo-Bar, Nana Kroo, and King Will's Town, which came to be regarded as their home district, though soon other offshoots developed along the coast, and particularly in Freetown, Sierra Leone

Economy

The kru economy is based on fishing and the production of rice and cassava. The coastlands are cut by a series of unbridged rivers that have restricted economic progress, so there has been a continuing exodus of young people to Monrovia, Liberia.

They tend to live on the Atlantic coast where they make their living as fishermen and subsistence farmers.

The Kru are known as stevedores and fishermen throughout the west coast of Africa and have established colonies in most ports from Dakar, Senegal, to Douala, Cameroon. With related tribes—the Basa and Grebo on the coast and the Sikon, Sapo, and Padebu in the interior—they occupy nearly one-third of Liberia. The Kru are thought to have entered the country from the northeast in the 15th to 17th century.

Renowned for their seafaring abilities, the Krus today remain a coastal people or live near the docks of Freetown where they work on ships or as longshoremen.

Religion

Large numbers of Krus are Harrist members of a religious group that preaches the Protestant doctrine of one William Harris, a missionary in Ivory Coast in the early twentieth century, along with traditional animist beliefs.

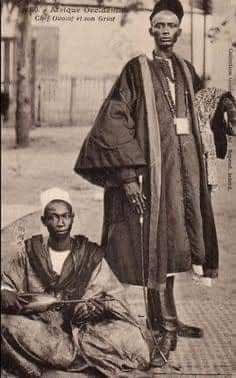

The first descriptions of a core group of Krumen's religion were done by missionaries notably James Connolly. But these accounts can also be augmented by more detailed accounts of the Grebo of nearby Cape Palmas who were linguistically and culturally related and were, by 1855 becoming Krumen themselves by going to sea and may have been as important in the overall culture as the core Krumen themselves.

The central elements of the spiritual universe of this region included a figure identified by missionaries as a high, creator God, named Nyesoa, spirits or deities associated with territories called, familial spiritual guardians called ku, and finally kwi or the souls of the departed who remained nearby and could influence events.

These spiritual entities were contacted through a class of people called deya, who underwent long and specialized training and apprenticeship to take up their office. They addressed problems both medical and spiritual using pharmaceutical and spiritual remedies.